Blog 3 Supplement – The Story of T.A. Mathews & The Monument of Louth, NSW

The following article was inspired by the CD “Firestone” by Tonchi McIntosh and Andrew Hull and the present-day people of Louth. The material is derived largely from a paper written by John Huggins following the “Back to Louth” Reunion of 1985. It also draws on discussions with Wally Mitchell, a long time resident of Louth, and material and articles provided by Shindy’s Inn. Information concerning the fate of the ship “The Great Britain” was sourced from Wikipedia.

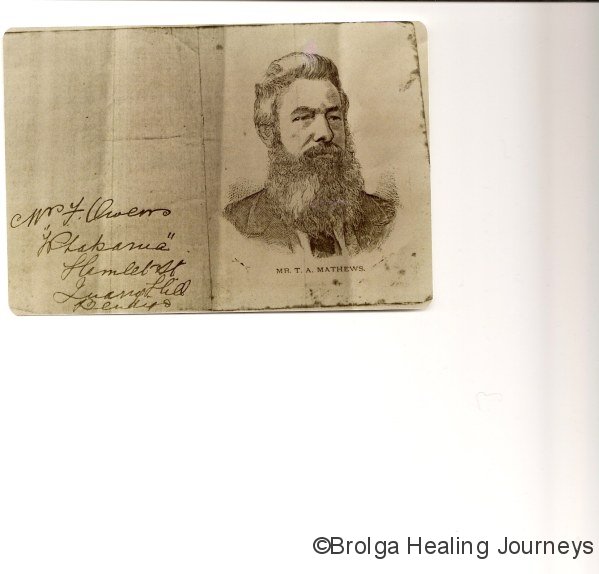

Our experiences of Louth have been constantly blessed by a sense both of serendipity and synchronicity. Time and again we’ve had chance encounters with people connected to the story of Louth. The latest occurred as I prepared to upload my photos of the Louth monument, to this site. With perfect timing, we received a kind message from Sue Huggins, a complete stranger to us, but whose research had gone into her husband John’s booklet, which formed the basis of most of the following information. John is a direct descendant of TA and Mary Mathews. Sue has been most generous in providing us with some early family photos, sketches and letters relating to this fascinating story about some of our pioneers. Thanks Sue for your help, generosity and very kind words of encouragement.

LOUTH, T.A. MATHEWS (“THE KING OF LOUTH”) & THE MONUMENT TO HIS FIRST WIFE, MARY

T.A. MATHEWS “THE KING OF LOUTH”

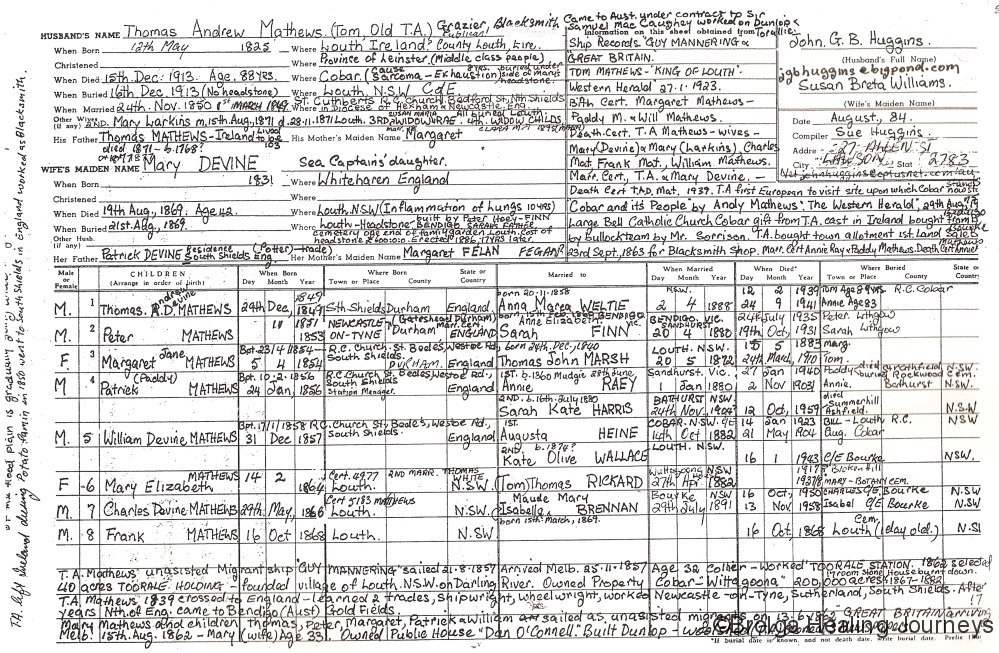

Thomas Andrew Mathews was born in County Louth, Ireland on 12 May 1825. He was well born, his predecessors being traceable for nearly 700 years. In Louth his people had a good estate. His father was also named Thomas and his mother Margaret.

When he had completed his basic education in 1839 he crossed to England, where he learned the trades of shipwright and wheelwright. This costly education, which was to prove so important later in his life, was acquired in the celebrated engineering workshops of the north of England. Firstly, he went to Newcastle on Tyne, then to Sunderland and finally his valuable apprenticeship was completed at the North-Eastern Railway Works, South Shields, one of the best mechanical schools in the world at that time.

Mathews had an ardent political nature and was chosen by the South Shields Liberals to convey their sympathy to the Smith-O’Brien party – a work which he performed so well that a great Liberal banquet was held in his honour shortly afterwards.

On 24 November 1850, Mathews married an Englishwoman, Mary Devine. She was a Sea Captain’s daughter and the happy event took place at St Cuthbert’s Catholic Church in North Shields. For reasons that are not clear, this was actually the second time they had married. The previous wedding took place in North Shields on 1 March 1849.

After having spent 17 years in the north of England, Tom Mathews decided to come out to the goldfields of Australia. This was probably prompted by the news which kept reaching Europe of the fabulous gold discoveries in Australia, particularly those at Ballarat and Bendigo in 1851. He decided to try his luck, sold his property in Louth, Ireland for about £3000 and brought his father over to Shields to look after his wife and children. He left sufficient funds to keep the family for two years, whilst he traveled halfway around the world to seek his and their fortune.

Mathews left England in 1856 and travelled on the ship “Guy Mannering”, to Melbourne. For the vast majority coming to Australia, the idea of settlement was never considered. For most, it meant only a voyage in a ship, a rapid run round a strange country, some large pieces of gold picked up easily, then home again rich and happy to family and friends. Upon arrival, Mathews proceeded at once to the Bendigo gold fields, where he worked at the Elysian Flat field without much success. So he tried storekeeping at Bendigo, but found this unprofitable, and after paying his debts, found he was the proud possessor of eight shillings.

Next, Mathews went up the river to Maidens Punt, now known as Echuca. Here he worked at his trade, buggy building for two years.

In 1859, he met a Mr R M Hughes, of the Bogan River Company who engaged him as a wheelwright. To reach his new employment Mathews had to travel via Melbourne and Sydney, then west to some wild and little known place on the Darling River. He travelled overland, camping out and having some very rough experiences along the way, especially with the employees of the Bogan River Company. One of them it is reported, the famous William Maher, or “Tipperary Bill”, was particularly good at taking a rise out of the new chum.

Toorale Station was the property of the Bogan River Co, and Mr R M Hughes was one of the largest shareholders. Mr Bloxam was then manager of this immense run. It was at Toorale that Tom Mathews was bound. In those days every station had to keep its own blacksmith and carpenter to make and to mend.

It is not hard to imagine how Mathews felt upon his arrival at Toorale. Here he was, separated from his family by vast time and distance, in a strange country with a hostile environment. His ingenuity was to be tested to the limit due to the lack of equipment. He made his tools using the iron from a derelict dray.

At this time, Mathews was troubled by temporarily failing eyesight. Here was the man who came halfway around the world to make his fortune and return home a splendid success. Now he had no money and his prospects were small. This is just where the pioneer spirit and iron will of Mathews came to the fore. From this humble beginning he was to triumph.

For three years on Toorale he worked in wood and iron – building boats, repairing drays, erecting huts, yards and so on; in fact, doing all the rough and ready work that the period called for. He worked for up to 16 hours a day and lived in a solitary hut. In those days there was no town for 800 miles from Wentworth to Walgett. Wilcannia and Bourke, as such, did not exist. When a bullock dray broke down there was nothing to do except take the vehicle to the nearest station and get the help of a tradesman. Such repairs were charged for, with the station book-keepers making out accounts just as the stores in the settled areas did.

Australia was then full of tradesmen of every kind who were able to do anything and everything when put to it. The names of these great workmen, and stories of their surprising inventiveness are even today handed down in the inland districts. Mathews was now working at what he knew best. There can be little doubt that he was as good and inventive as the most proficient. He commenced to save his money and slowly but surely success came his way.

By this time in 1862 Mathews had come to know and love the life in the out-back, so he sent home for his wife and family to come and join him. As he had saved enough money he started blacksmithing on his own account near where the town of Bourke now stands, and not far from where Fort Bourke had been erected by the explorer Mitchell in 1835.

Mathews bought three blocks of land in the first sale of town land in Bourke on 23 September 1862. This significant event had followed 2 years of agitation by Thomas Dangar and later, Joseph Becker, to establish a town where there were already stores, a hotel and dwellings. The township had been marked out in May that year and the first government officials appointed shortly afterwards.

TA & MARY REUNITED IN AUSTRALIA

Mathews’ wife Mary came out to Australia with the children on the ship “Great Britain”, which berthed in the port of Melbourne. Also on this ship was Mrs G A Carstairs, wife of the holder of Mallara station, on the Darling. She was accompanied by Miss Mary Knight who, some years later, was destined to marry Mr DWF Hatton, one-time stock inspector at Bourke. Unknown to each other, these good folk were all heading for the Darling River, and were fated to be numbered among the pioneer families.

From there, the family traveled in a van to Echuca, then journeyed down the Murray River to Wentworth in a steamer appropriately named “Settler”.

Meanwhile, Mathews, now 37 years old, set out to meet his family. He rode one horse and led another with the pack, from Bourke to Wentworth. Finally, after six long years of separation he was happily reunited with his wife and children (Tom (aged 13), Peter, Margaret, Paddy and Will).

It was now Christmas 1862 and Mathews purchased a spring cart at the junction town– a scarce vehicle and much sought after at that time. Leaving this last big outpost of civilization, Mary and the children traveled in the cart over the long journey to Bourke. Mathews recommenced his work, at the same time improving and increasing the stock of horses and cattle he now had.

At this point it is interesting to reflect on a little of the history involving the “Great Britain” and the “Settler”, both of which were part of the journey of Mary Mathews and her children.

The Great Britain, of 3,450 tons was by far the largest vessel of its day. It had an auxiliary screw propeller and an all iron hull and made its first and made its maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York in July 1845. After several misadventures and refits, it became a vessel with three masts, full clipper rig and single funnel. This was the profile retained and recognized during voyages to Melbourne and elsewhere between 1853 and 1875. The vessel was used for transport service during the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny. The Great Britain completed one outward voyage in 1860 in the record time of 55 days. She finally ended her days as a coal hulk in the Falkland Islands. Salvage was organized in 1967 and the hull was moored for a time on a pontoon in the River Thames near Tower Bridge, before being transferred to Bristol Harbour where she was restored and is now a maritime museum.

The “Settler” was built in Port Adelaide in 1861 to an American design which proved unsuitable to Australian inland rivers and in 1863 she was sold to Brisbane owners and she ran on the Brisbane River until she was abandoned in 1884. Few of the Echuca steamers traded on the Darling, and in time of high water, most passengers and cargo trans-shipped at Wentworth into smaller ships for onward travel. This probably explains why Mathews met the family at Wentworth. It was said that the Settler looked like a two storey house!

The Mathews family called Bourke their home for only two more years as Mathews took up a 40 acre selection on the Darling River on 19 January 1865 which he named Louth in memory of the county he had left as a child. He continued to increase his stock. He put up a public house which he called the “Daniel O’Connell” (named after Ireland’s pre-eminent political leader in the first half of the 1800s. O’Connell, known as the Liberator, is remembered in Ireland as the founder of a non-violent form of Irish Nationalism and for mobilising the Catholic community into a political force). This place he painted white, doing the work on moonlight nights, as it could not be done in the daytime because of the summer heat.

His first stock of wines and spirits was almost drunk up in one week by four men, who shouted all and sundry. One spent £120, another £80, and the others 20 each. This was in the early 1860s, and they were “roaring times” in the backblocks.

Leaving Mary to look after the public house, and his sons to see to his stock, Tom Mathews had the time to devote to horse-dealing and contract work. He built the Dunlop woolshed and shifted houses across the Talyawalka – an anabranch of the upper Darling – steering the huge loads with a long pole, like a steer-oar. He ran a smithy and went anywhere; in short, to build anything. His sons were helpful and, like many others, had to forego their chance of a formal education in order that their father might succeed.

In 1866 Mathews increased his holding at Louth to 200 acres and conceived the notion to found a town. The original forty acres on the river bank were cut up into allotments; houses were erected upon some of these. A bonded store was started, where merchandise was stored against low rivers. Steamers stopped at the door. Trade had its ups and downs, but Mathews kept so many irons in the fire that he managed to pull through and was known up and down the river as “The King of Louth”.

In November 1867 another land sale was conducted in Bourke and Mathews was again a buyer. This is probably when he purchased 10 allotments reported to include half the town. His funds came from the proceeds of the sale of a second hand spring cart. One of the allotments was sold in 1884 for £2500, certainly evidence of progress in the far west.

Mathews prospered and other developments followed. In December 1867 he took up a run of 200,000 acres, the Wittagoona selection, and made it one of the best stations in the west. This extensive property, known variously as Wuttagoona and Wiltagoona, stretched inland in generally a south eastern direction from the Darling until its backblocks encompassed the Kubbur area (the Aboriginal name for the area later named Cobar). The original homestead was built by Mathews and consisted of 17 rooms built of stone. The station became an outpost in the further development of the west. In the early 1880s it was reported that the property including stock was worth £150,000. In addition, Mathews owned much of Louth, whose allotments he had begun to sell. He also owned another station of 16,000 acres in the vicinity. It is said he spent £75,000 in improvements to Wittagoona alone.

Mathews had a rather rough and gruff manner, and was respected rather than liked, but also possessed a remarkable wit. He seemed to have a way with Aboriginals, which gained their confidence. He always paid the Aboriginals who worked for him and made a law of his own regarding them (as there was no other law around at that time). No white man was supposed to go near the blacks’ camp on his station. If one did, then Mathews would deal out his own brand of justice by knocking him out! Otherwise he allowed the Aborigines to hand out their own punishment and nothing more was said.

On one occasion when a white woman was having a baby, her husband and another man with him panicked. Someone went for Mathews who was not keen on the job and he started to swear as he tried to deliver the child. A black tousled head peeped through the door and said:

“You catchem white pella pickininny Old Man Mathews?”

Mathews replied “C’mon, c’mon Mary, you do this and wash your —–hands and you useless —— you keep up that hot water”.

“Mine been washinup all night old Man Mathews” she replied.

When he heard this he sent to the blacks’ camp skilled in their own way to do the tribal work. So the first obstetric nurse of the white man’s time went into action. A bullock and a bag of flour was delivered to the blacks’ camp that night.

In 1870 three earthmoving contractors came to Louth and enquired of Mathews at the “Dan O’Connell” Hotel asking for directions across country to the “Overflow” Station, where they said some work awaited them. Mathews directed them to his Wittagoona Station, which he had recently acquired, and was about 40 miles south of Louth and in the direction they wished to go. When they arrived he said they would be supplied with flour, tea and sugar, a bullock would be killed and salted for their use on the trip and an Aboriginal named Boney would accompany them to the Cobar waterhole about 40 miles further on.

This Cobar waterhole was known to his son, Tom Mathews Jnr, and George Goldfinch who had been brought there by the same Aboriginal 2 years before on a search for horses strayed from Wittagoona. At that time they had come across lots of “gins” digging for yams who screamed when they saw the white men. A hunting party of Aboriginals ran out to cut them off. The blackfellow Boney galloped forward shouting to them in their own language and Tom jnr and his mate heard him say a couple of times “Old Man Mathews”. After this the blacks returned to their hunting and the women to their digging.

The three contractors were Thomas Hartman, a Dane, Campbell, also Danish, and George Gibbs, a Scot. In the party were several other men, one being a Cornishman. When they reached the waterhole, at the spring on the northwestern side of the hill, the Cornishman remarked on the stone around the place. The others, also having some mining experience, were interested. There was a red deposit and white clay, both of which the natives used for corroborees or for war paints. The place was called Cobar. Boney returned to Wittagoona and the men continued on to their next place of call, Gilgunia. They took some of the stone with them and a family at Gilgunia had a forge. These people named Kruge were also interested in the specimens and after smelting some in the forge were convinced it was copper.

Campbell, Hartman and Gibbs returned to Bourke and approached a businessman Joseph Becker, who with a Mr Bradley (of Cobb and Co), Mr Russell Barton, and “Gundabooka Smith” took 40 acres of the area and so formed the first Cobar Company. About March 1871, the Government Surveyor, Mr Evans, came to survey the spot, and Harry Cornish, later to be a well known character in Cobar, placed the first survey pegs. No work was done for some time after the survey until 3 tons of ore were taken to Louth by bullock wagon and from there by the steamer “Princess Royal” to Port Adelaide, for treatment to determine its value and thus the true significance of the ore discovery.

It is believed that TA Mathews (Old TA as he became affectionately known) was most likely the first European to visit the area where Cobar now stands.

The man recommended to manage the Cobar Copper mine was Captain Thomas Lean who had impressive experience in the mining industry. In his first report to the four mining partners, lean told them of his impression of the mine. He said that he had seen the principal mines of this country and he considered they had the greatest copper lode within the confines of Australia. He further emphasised this opinion by stating his belief that no child then living would survive to see the bottom of the lode. Copper mining continues in the Cobar district to this day (2007).

Thus the Cobar Copper Mining Company was born and exploitation of the ore began in earnest under Lean’s direction. The ore was quarried in huge blocks and dispatched to Louth or Bourke by bullock team. With his knowledge of the district’s water-holes and suitable tracks Mathews carted many lodes of ore to Louth and returned with ship’s tanks on his wagons brimming with river water. At the river ports the ore was stacked until the river was navigable, when it was conveyed to Halletts Smelting Works or the other principle smelters at Port Adelaide. This particular mine closed down in 1874, mainly because of water supply and transport problems. Thomas Lean left the mining industry and selected a small pastoral holding near Cobar and called it “Hilda Vale” after his daughter. This later became the property of Thomas Mathews jnr and he called it “Maryantha”.

The Louth Post Office was established on 1 March 1869 and was run by TA Mathews. Despite opposition it was closed on 1 July 1871. A petition signed by steamboat owners, Captains, teamsters, mine managers and other important people failed to change the decision of the Department although they claimed the new copper mine would bring the Postmaster a great deal of extra work. Tenders had been invited for a mail service to the Cobar Copper Mine and the Department considered there was no reason to reopen the Louth Post Office.

We will digress a little now from the main story and record the words of a reporter from the “Town and Country Journal” of that time. It gives some colour and feel for the country which relates to our tale. The correspondent writes in 1872:

“On Thursday morning, about the middle of May, I started for Louth on the River Darling, in company with Mr TA Mathews, we passed Fandon, twelve miles, Mr Forlonge’s station, without having a glance at Mr F Wall’s famous wool-washing and scouring apparatus, and after getting over fifteen miles more, we camped for the night at Yanda, (Cobb and Co’s). Red Bank, Gundabooka, Tooralie and other stations we passed in succession, passing also the steamers Wentworth and Providence, still lying in ordinary till the river rises. I saw nothing remarkable about the country beyond what I had seen elsewhere, but I did see an unusual number of blacks, some at stations and other places, not one of whom had even the fragment of a Government blanket to cover him. Who can answer the question ‘When were the blacks on the Darling River supplied with blankets?’ There is shameful neglect somewhere. When winter is half over I hear blankets are coming.

At last we reached Louth and its renowned “Dan O’Connell” Hotel, of which my companion was the proprietor. It stands at the junction of the Wilcannia, Bourke and Lachlan roads on a portion of 320 acres of purchased land – land that will grow anything. Stables, carriage-shed, meat-house, sawpit, smithy, stock-yard, garden, a neat cottage, a hut, and other buildings, one close to the hotel; and at one end of the garden there is a family cemetery.

Mr Mathews is not only a publican but a grazier, and his cattle, as I saw them, are ‘as fat as moles’. He owns, perhaps, more purchased land as he certainly employs as many men as any other person on the river.

The Rev. Father Nugent arrived from Bourke on the Saturday evening, celebrated mass the following morning and, after dinner, performed (to two) the pleasing ceremony of marriage, the bride being Miss M Mathews. (This was Margaret Jane who married Thomas John Marsh on 20 May 1872.)

It was decided by Mr Mathews that I should neither ride on horseback nor walk to Cobar, but accompany his teams that would be going for more copper ore in a few days, taking water with them. This ore is brought to Louth and stacked on the bank of the river awaiting the steamers. I suppose there are now 100 tons there. A jetty will soon be erected and a shoot to enable the steamers’ barges to be loaded more speedily.

On a Thursday at noon I was on the main road leading from the Darling to the Lachlan, once a good route for travelling stock to Melbourne, being 100 miles shorter than any other, but now disused for want of water. But for this fault, the country is magnificent. The first night we camped at Mulya, 25 miles, where Mr Mathews has two men employed in sinking a well. Here we left three large tanks of water for our horses on their return trip. The next morning after giving each horse two buckets of water, we started and reached Wittagoona, 35 miles, late at night. Wittagoona, pronounced Wittygoona, is a sheep and cattle station belonging to Mr Mathews, and the aspect of the country near the head station is really beautiful. To the west there is a continuation of the long mountain range which kept in our view nearly all the way from Louth. There is an abrupt chasm in the range where huge boulders of red granite appear to have been tumbled one over the other in wild confusion. From these rocks, most picturesque to look upon, a constant supply of water is at all seasons procurable. On climbing them, nearly to the summit, I found to large basins filled with clear water which came trickling down the crevices of the rocks above. From the upper basin the water dripped into the lower one, and thence to one level with the ground accessible to sheep and cattle. By means of a hose the teamsters were enabled to fill there tanks and hogsheads from the second basis – a difficult task entailing much delay. Six teams were taking in water, and no sooner had they taken in their supply than a steady rain commenced and continued for upwards of two days. The teamsters had thus been working for love as they threw all their water away, well knowing that the clay-pans and other places on the road would supply them. The two teams, therefore, which had come from Cobar for water, now proceeded with two others to Louth, each taking 3 ½ tons of copper ore. Wittagoona appears to be an intermediate depot for the ore, scores of tons in bags being stacked near the hut. It is intended that one set of teams be employed between Cobar and this station, and another set between here and the river; Mr Mathews being the responsible person for receiving, weighing and delivering to the steamers.

The rain made the road heavy, so the teams halted for a few days. I went by a track to the top of the range and found the country on the other, or western side, much higher and level. A small creek led water to the rocks from the top of which the view from below was grand. there is a cave on one side, the inner walls being painted or daubed with rude images of the natives in the attitude of a corroboree. The undulating character of the country west of the range is very beautiful, and it is to me strange that the creeks do not contain water. Certainly the soil is very absorbent, retains moisture for a considerable time, and preserves the bush, herbs and much of the grass in a state of freshness.

At length we started for Cobar, four teams leaving at the same time for the river with ore. In ten miles we pulled up at Buckwereena Creek and camped. Next morning, we started early, meeting with nothing save a few emus, paddymelons and a native dog. We passed Mathews’ flat, where a large tank is being made and which promises, from the nature of the country, to be of great value as a reservoir. [A tank, or ground tank, is what we usually refer to as a dam.]

When approaching within about four miles of Cobar the ground becomes more gravelly. Large pieces of quartz could be seen on each side of the road, and an occasional ‘blow up’ of rich-looking quartz in large quantities was met with, particularly on the ridges. The surrounding country was undulatory, well grassed, nicely timbered, and supplied with fine green bush and herbs of many descriptions. In front, at some considerable distance, there appeared to be a long ridge of hills, well timbered, running north and south. At the southern extremity there is a small mountain which some people call Mount Elizabeth. Descending the range we found ourselves on what may not be inaptly called ‘the plains of Cobar’ and travelling about another half mile brought us in full view of the Cobar Copper Mine.”

On another occasion the “Town and Country Journal” reported in part, relating to the Cobar mines:

“There are two roads by which the ore is conveyed to the River Darling, one called the Bourke Road, the other the Louth Road; the former is considered to be one hundred and twenty miles, dangerous to risk teams upon in very dry weather, and too boggy to travel over after heavy rain. Five tanks have been sunk by the Cobar Company on this road. The Louth Road is considered to be one hundred miles long, with a better reliance on water. It is generally admitted that this is the better road of the two for carting copper ore to the river, and it is obviously the more desirable if the interests of shareholders are to be considered, because Louth is seventy miles lower down the Darling than Bourke, or about 200 miles by the river’s course; the freight from Louth is lower and there are many occasions on which steamboats could venture to Louth when with a higher level, they could not reach Bourke owing to the rocky barrier at Toorale and other obstructions. Indeed some consideration is being paid to the formation of a new road from Cobar to tap the river about 30 miles below Louth but many difficulties will present themselves. There is a much shorter bush road to Louth, but the teams have only used it once or twice. One use the telegraph at Bourke will be to the mines, is in notifying to the river steamboat owners in Adelaide, or Captains of steamers at Wentworth or Goolwa, any good fresh flow in the river at Walgett or Brewarrina. But whether the Bourke or the Louth road be used, there must be a more reliable class of teams engaged, nd greater regularity adhered to. It would also be an advantage to the mines to have a recognized depot at some portion of the Darling at, or a little below, Louth for the reception of stores brought up by the steamers. At present there is a receiving house at Louth for ore intended for shipment.”

Whilst all the mining and associated activity was taking place at Cobar, Mathews had his other enterprises also to keep him busy. Old TA had started a smart little paper called the Louth Liberal, and later when he took an interest in Cobar and the mining prospered, he started a newspaper called the Cobar Herald in 1879. It was the first local paper, and he sold it soon after he had set it up and got it going. This “Cobar Herald” existed until October 9th, 1914, just after the outbreak of the Great War. In the late 1880s he started a third newspaper, in Broken Hill, which he afterwards sold to Mr Reid, one of the millionaires of that place.

Louth grew into a prosperous and useful town, mainly through the exertions of one man and his family. It must be acknowledged that without his family he could not have accomplished the work. Louth never became a large centre, as Bourke grew to be the major settlement, particularly with the arrival of the railway in 1885. However it proved to be very useful because of its placement lower down the river and played its part in the growth of the district.

As mentioned earlier, Mathews seemed to have a great influence with the natives. Some of his grandson Andy’s anecdotes are worth recalling. One day a white family was passing through the area when they lost a small boy in the bush. When Mathews heard about it he sent a message to the blacks’ camp and in a very short time about 200 Aborigines paraded near his homestead. Some of them were quite wild and had not been at the station before; each carried a boomerang; they stood around in groups, with the wilder ones on their own. The station blacks moved about amongst them briefing them on the job. They then went to the spot where the child was last seen, and immediately picked up the tracks. The Aboriginal who was on the track lifted his boomerang before him and started to follow it. The others spread out on each side of the tracker who was carrying the boomerang, and did not bother to look for tracks, unless the main tracker indicated by dropping the boomerang to his side, that he had lost the trail. They never stopped walking. Old TA and his sons, together with the other white folk on the station were close behind the natives on the track, when one of the station blacks said “that white feller piccaninny soon tumble down”. A short distance further on they found the child exhausted beside a tree, but otherwise unharmed. That night sugar and flour was sent to the blacks’ camp from the station store and around the campfires the search for the child was again enacted, as was their custom.

During one dry period Old TA gave the tribe’s medicine man Jacky Boolierie two figs of tobacco to make it rain. Jacky made it rain and it poured down all night. Jacky came in the next morning to stress that the job was a good one. Old TA agreed that it was and promised two more sticks of tobacco to keep it going. This Jacky did and the drought was broken.

A Chinese cook was employed at the station for a few years after Mathews had formed it. A time came when the Chinaman planned to return to his native land. Old TA started one morning on the forty mile trip to Louth with his buggy and pair with the Chinaman as passenger. The day was hot and dry, the dust rose from the bush track and Old TA began to get thirsty. However, he was too independent to ask the Chinaman for a drink from his waterbag, which hung from the dash of the buggy. Finally, thirst got the better of him and he asked the Chinaman for a swig from the bag. “Welly good. welly good” said his passenger. Old TA lifted the bag and took a long draught; he spluttered, coughed and swore. Then he swung the bag and hit the Chinaman over the head with it, saying “You ——–, you’d poison a man! Poison a man!” The Chinaman still protested that it was “Welly good” and explained he had boiled a sheep’s head before leaving the station and made a broth with it, with which he had filled the water bag.

Old TA had a well-bred mare as his own saddle-horse, and he would start from Wittagoona early in the morning and reach Louth in the afternoon, forty miles away. The mare would walk smartly along the track, and at times the old chap would break the monotony by reading a book, and when he got absorbed in the book, the mare would pick grass from the side of the track. If the old chap was really deep in the book she’d settle to have a feed. When he realized what had happened he’d swear and they would start down the track at a gallop.

When the bushranger Ben Hall was shot dead at Forbes in 1865, his sister Mrs Huddy was at Bourke and Mathews gave her his own horse and a letter to any squatter along the way saying he would be responsible for any change of horses she would need. She rode non stop through the bush from Bourke to Forbes. That’s a little-known piece of Australian history. She was reputed to be a wonderful horsewoman.

After he started Wittagoona, Mathews employed a station bookkeeper, an Irishman who was an ex-Indian Army Officer. They decided they would make a still; the sugar in those days not being as refined as it is now, was of a coarse grain and yellowish in colour. Old TA could do just about anything with tools, as we know from his trades experience. He made the still and they set some sugar to ferment so as to make some rum. As the distillate began to drip from the pipe they would sample it and the bookkeeper said “As good as can be cracked under a tooth, Mathews”. Old TA replied “Yes, yes it’s damned good”. This went on until they were both on their knees beside the still as it bubbled on. Finally they lay beside it, out cold. It must have been a potent brew. The still steamed on until the fire burnt a hole in the bottom, when the still went dry. Mathews’ sons and some of the other station men found them lying next to the still and proceeded to put them to bed. They threw the still on the rubbish dump together with the spoilt sugar. Some years later Harry Knight snr of “Mopone” purchased Wittagoona and he mentioned that there was a strange sort of contraption much rusted on the rubbish dump. He said “It seemed to be a sort of twisted pipe on a kettle sort of thing”. It’s a pity Old TA’s still never got to make it to the Cobar museum. It was his first and last illicit liquor still.

When the big flood came down the Darling in 1870, Old TA started building a boat as rumours said that the flood was increasing. The old man kept working on the boat without resting. The Police at Bourke had asked him if he could finish it as soon as possible because there were some people marooned on some sand hills. He kept working on the boat, only taking time to snatch some sleep now and then next to the bench beside the boat. The water kept slowly rising into the workshop and when the boat was finally finished, the water was up around his knees. He climbed onto his bench exhausted when the police took the boat away. This was a feat of endurance by Mathews that would have fully tested even a lot younger man.

Mathews also had a fine sense of humour. When he built the Dan O’Connell Hotel at Louth in the early 1860s he was required to display a sign showing his name and the words “Licensed to Sell Fermented and Spiritious Liquors”. This he did with the addition of another line which read “all customers at this hotel are allowed the unusual privilege of watering their own grog”. It was true to label.

One day Old TA paid a visit to his son Charlie’s place in Cobar. One of his other sons, Tom, and his boy Andrew decided to call on the old man. It was a very hot day and when they arrived they found the old man lying on a bed on the back verandah with a hat over his eyes. His son used the same expression Mathews had used to the boys when they were younger “It’s time you were up and doing”. Then the old man removed his hat and exclaimed “Why damn it, it’s my son Tom and Andrew”.

At the coming of the railway to Cobar in 1891, there was a banquet at one of the hotels and the usual speeches were made by the citizens of the time. One of them, Jerry Oakden, of “Laria” had the floor and delivered quite a lengthy speech. Old TA was the next one due to speak and became more and more impatient. Finally, when at last his turn came, he rose to his feet and thundered “Mister Chairman, following the last gentleman who has talked so much and said so little…”. They poked their whiskers out and glared at each other.

A large bell was donated to the Cobar Catholic Church by Mathews. He had it cast in Ireland and it was brought to Cobar from Louth by a bullock team.

MARY DIES & THE GRANITE MONUMENT ERECTED (EVENTUALLY)

Death was never far away in those days, particularly before the advent of the medical treatment that we have today. Mathews’ wife Mary Devine died from “inflammation of the lungs” on 19 August 1869, aged 42. She had the illness over a period of ten years. Mary had borne three more children after she had arrived in Australia. They were Mary Elizabeth in 1864, Charles in 1866 and Frank in 1868 who sadly died when only one day old.

When Mathews was 46 he decided to marry for the second time. This was to Mary Larkins, aged 22, who had originally come from Victoria. They were married at Louth on 15 August 1871. The pressure of the outback life must have been too strong for Mary as she died only three months later. A coroner’s inquest found that she had died from taking strychnine poison.

Nearly two years later in 1873, and now aged 47, Mathews married for the third time. The ceremony took place in Bourke on 28 March 1873 and the bride was Susan Maria Raey, a widow aged 33. She had five children from her previous marriage. They were Charles, Annie, William, Lily and Emily. An unusual circumstance was that in 1880 her daughter Annie married Mathews’ son Paddy. Susan Mathews died on 22 November 1891, aged 52.

In 1895 Mathews married for the fourth and last time, a widow, Clara Childs, whose late husband was a doctor. They were married in Bourke on 12 March 1895. Clara was a domestic at Mooculta, near Bourke. She was born in Windsor, England the daughter of Robert Ross, and Mary Anne Webster and was aged 41 when she married Mathews.

Mathews decided to commemorate his first wife Mary and ordered a granite monument to be built by his friend Peter Hoey-Finn of Bendigo. Peter Finn was born in County Monaghan, Ireland, in 1834 and came to Australia in about 1855. He had launched into his work as a monumental Sculptor and stone-cutter in 1863. His business grew rapidly until by the late 1880s his yards, which were over an acre in extent, contained perhaps the most extensive polishing plant in the southern hemisphere. So great became his business that at one time he had at least 150 men working for him fulfilling some of his large granite contracts. In 1880 his only daughter Sarah, married TA Mathews’ son Peter, in Bendigo.

PLEASE CLICK ON THE FOLLOWING TWO LINKS TO SEE PHOTOS OF PETER FINN & MARY ELIZABETH (DAUGHTER OF T.A. & MARY MATHEWS). TO RETURN TO THIS ARTICLE HIT THE “BACK” BUTTON.

Mary Elizabeth Mathews, daughter of Mary Devine and TA Mathews

The monument was to be transported to Louth by the steamer “Jane Eliza”, a riverboat that held a special affection in the memory of those who knew her. She was a vessel of 120 gross tons built in 1867 at Moama, opposite Echuca. She set out for Morgan in May 1883 with the monument and with building materials destined for a new hotel in Bourke. The Jane Eliza ran into one of the Darling’s most drastic lows and was stranded in a succession of waterholes. She was stuck finally in a waterhole at Tilpa for two years. To make a living the skipper harnessed the boat’s power to run a riverside sawmill and cut timber.

The river eventually rose enough to let the Jane Eliza continue her journey to Bourke. She finally arrived in June 1886, over three years after her departure. The railway had arrived in Bourke nine months earlier and timber for the new hotel had reached the town by train from Sydney. The hotel had by now been built. The Captain had no alternative but to auction the material as the man who had ordered it had left town. The building materials were bought by a contractor who hauled them off by camel train to Broken Hill, where they suffered the particularly incongruous fate of being used to build a church.

Meanwhile, the Jane Eliza had a dramatic change of fortune. She loaded up at Bourke with three barges in tow filled with wool, and ore from Broken Hill mines. She caught the peak of a Darling flood and thundered back to Morgan in three weeks. She had now established two river records – the slowest trip up to Bourke and the fastest back.

When the Jane Eliza had been marooned at Tilpa, Old TA had finally decided to bring the monument to Louth by bullock team. The delivery was, of course, three years overdue. By this time Mathews had married his third wife, Susan Raey. Those who tell the story say that his new wife presided over the ceremony of the monument’s erection while her husband staged a banquet to the memory of his two dear departed, and coupled with their names the health of their successor!

When the monument was to be erected in Louth, Peter Finn came from Bendigo to personally supervise the construction. He brought all his own materials, tools and appliances. He came by steamer under his own care. All the associated scaffolding and timbers were left in Louth. After the monument was erected, Finn went to Cobar to spend a few days with his daughter Sarah, who was married to TA Mathews’ son Peter.

The monument cost £600 and was reputed to be the handsomest and costliest of its type to be found anywhere in the colonies. The grey granite, with a golden fleck throughout, was quarried from Phillip Island in Victoria. The 7.6 metre high memorial headstone has a 1.2 metre high Celtic cross on top, which is ingeniously positioned so that at sunset each day it reflects an unusual halo-like image, which can be seen from various angles on the Louth common, depending upon the time of year. On the anniversary of the day Mary Mathews died (19 August 1869) the sun reflects from the cross to the spot where the house (“The Retreat”) was in which Mary lived. Nothing now remains of the house, save some old bricks and rubble.

The Captain of the Jane Eliza was believed to have assisted Peter Finn in accurately positioning the monument to capture the sun’s rays each day at sunset and to ensure the reflection to “The Retreat” on 19 August each year.

BACK TO THE STORY OF “TA”

With strong loyalties to his homeland of Ireland, Mathews did not hide his sympathies. He had opened the Smith O’Brien Hotel at Wittagoona on the Louth track in 1874. Smith O’Brien was an Irish Republican patriot who was exiled to Tasmania for a number of years. The “Wittagoona” selection that Mathews had taken up in 1867 and built into one of the best stations in the west was eventually lost by him. There are a few different versions of how this came about. One story is that he just walked off the property in 1882 after the land had been devastated by plagues of rabbits and a fierce drought. Another interesting tale has been passed down through Lil Earngey, a descendant of Old TA’s daughter Mary, who was the first white child born in that part of the Darling River country in 1864. She married Thomas Rickard in 1882 at Cobar, his father having worked for Mathews as his bookkeeper at Wittagoona. It seems the government had decided that Mathews had taken up too much land and now they wanted some returned. With the pride and stubbornness that had helped him tame that rugged country, Mathews refused to relinquish that land. He decided to fight his case through the Australian courts and lost one battle after the other. Finally, in a last desperate bid, he mortgaged Wittagoona to the Bank of New South Wales to finance his case before the Privy Council in England. Unfortunately he lost his quest and in the process, Wittagoona.

However, Old TA Mathews survived this major setback. He still had many other successful enterprises that kept him going. He owned stores and various other businesses in Louth, Cobar and Bourke and his capital at one time gave employment to at least 350 people in one capacity or another.

It appears Mathews at one time held political ambitions. It reminds us of his early political activity in England with the Liberals. A small biography written in 1884 seems to be a laudatory account of his life aimed at furthering those desires. After giving a colourful description of his life the book concluded with the following quoted lines:

“Possibly rough and off-handed in his style, self taught in a hard school with regard to colonial enterprise, with a genuine disposition when rightly approached, but with a shrewd common sense that nothing can impose upon. Thomas Mathews has proved himself a man cut out for pioneer work in this country; and when it is remembered that he succeeded where hundreds of other failed, all the more credit attaches to his success. At the last general election Mr Mathews was nominated for a seat in Parliament to represent Bourke, and his election was regarded as a certainty. The battle for second place, it was thought, was between Messrs Barton and Machattie; but, as is often the case, the certainty lost Mr Mathews hundreds of votes, and his election also. At the next election, however, Mr Mathews will be nominated, with the certainty of a very different result.

Since the above was written, certain proceedings have taken place at Bourke, with which Mr Mathews has been identified, and which form another chapter in his history. It appears that a death of a married lady (Margaret Marsh nee Mathews) in Mr Mathews family took place, apparently with some suddenness. The lady had previously had medical attention, and it was known to the family that death had arisen from purely natural causes. Hence when, from malice or unpardonable ignorance, an inquest was set afoot, with post mortem examination of the body, the friends strongly objected to the latter proceedings, and carried out the funeral obsequies. The family expressed the greatest repugnance to what they regarded as an inevitable unnecessary mutilation of the body of their lamented relative. This was an infringement of the law, no matter whether the inquest originated in base motives or not, and legal proceedings were instituted against Mr Mathews and his son, with the result that the former was fined £100, and the latter a smaller sum. The money was immediately subscribed on the spot; but Mr Mathew declined this evidence of substantial sympathy, being satisfied that he had by no means forfeited the respect and esteem of the people among whom he had so long lived. In due course the case was reported to the Minister for Justice, who on perusal of the facts, intimated that the fine of a shilling would have fully met the merits of the case; and he now, we understand, directs a refund of the money, the judge who tried the case, strangely enough, advising that course to be adopted. This little incident, as already stated, is but another chapter in the history of Mr TA Mathews. As through all the difficulties and struggles of his early life he came out welded into a better man, so, in these last proceedings, where his character and motives have once more been under the fierce glare of public light, he came out with a disposition marked by the strongest affection, and a will exhibiting insensible inflexibility to every kind of threat and every species of annoyance.”

It is remarkable that we do not know what became of “Old TA’s” political ambition and have little material on this latter part of his life, when there is such a fund of information on his early days available.

After a long, colourful and strenuous life, Thomas Andrew Mathews died in Cobar on 15 December 1913 at the grand age of 88. His father had lived to be 103 years old. Old TA’s body was carried to his beloved Louth in Bobby Simpson’s REO truck, one of the first in the area. According to a descendant who witnessed the burial as a child, the dirt was dug out from under the side of the granite monument he had erected for his wife Mary, and his coffin was laid underneath. This is where he lies today, at rest, together with his wives and baby son. A man who had incredible energy and foresight, the “King of Louth”, one of the pioneers of the West.

Thankyou for printing the story of Old T.A. my husband, ancestor.

John wrote the book in a week from my research for the Mathews family reunion at Louth 25 years ago. Sadly a lot of the old timers have since passed on but the extended Mathew`s family still continues to grow in all states, mainly on the land.

If any descendants would like to make contact with someone regarding the family tree, please feel free to pass on our email address.

Good interesting site.

God bless,

Sue.

I enjoyed reading the information provided regarding old T.A.

As I am a descendent of T.A I would be gratefull for more

information.

Dear Peter,

They are excellent photo`s of Mary Mathews monument, the best I`ve seen so far. Your site is the only one telling the full story of the King of Louth. The Mathews family are very grateful to you as would be the little back-of-Bourke, town of Louth, NSW.

“Firestone” is a wonderful CD and musical background by very talented artists. I think “Firestone” is still available from Andrew Hull, Bourke, who has a web site which includes words from the songs about the Mathews family and those early days.

Everyone loves an outback love story, maybe one day they will make a movie about Old T.A Mathews and his Mary Devine.

Thank you once again for your kindness and help.

Happy travels.

God bless you and yours,

Sue.

Thank you Sue for your kind words. I am glad I have been able to play a small part in keeping this inspiring story alive.

Hi my grandmother was Margaret Mary Wallace Devine Harland (nee Mathews) of Bourke. My mum Thelma found this book from the reunion and only on the weekend produced it and I read it for the first time. I thoroughly enjoyed it and it was great to ready about my heritage. I now want to travel to Louth. I spent my childhood every year in Bourke but have never been to Louth.

Sue, I think your daughter Tara told me a little bit of this family history once. Can you please let her know I’m also ‘out and about’ (since November 2007) and give her my email address if she wants it? Many thanks.

How fabulous to find such a comprehensive history of my ancestors online! As a child in 1983 I travelled to Louth for a family reunion and so remember a little of the family’s story… I remember Sue Huggins even then had been compiling her research. At my mothers urging this morning following a conversation on family names, we followed a google search on Mary Devine and found this fabulous post. Thanks so much. I am a descendant of T A’s son Peter, probably 5 generations.

Thank you Lil. It’s wonderful to be contacted by another descendant of TA. Even though I’m not related to the family, the story fascinated and touched me so deeply I wanted to do something to honour it and make people aware of it. And of course, Louth is a magical place which we fell totally in love with!

Great story.

I have friends at Louth, (Wally & Margaret Mitchell). On my first visit to Louth in 1974 Wally took me to the cemetry to see TA’s wife’s grave. The reflection off the cross is something to see. I hope to be in Louth in April for a week or more.

regards

How Proud to be a desendant of this amazing man,my grandmother Augusta Olive Hudson told me many stories of OLD TA. One of the locals were discussing old TA at A charity event and she told any one that could hear, that TA lost his land due to the rabbit plague, I repeated the story to nan (Augusta) she said that story was not true, that it was in fact the government and land tax .My nan was born in louth, and then moved to BOURKE were she lived to her last days.

I am Stan Mathews grandson.

I live in Bourke and frequently visit Louth with my kids.

It would be great if any of mathews clan has a family tree they would like to share.

Hello,

I am researching my husband’s family tree. There have been a few variant spellings of the surname- namely VALLELY, VELLELY VELLELEY.

I believe Peter HOEY-FINN was married to Mary Jane VALLELY the youngest daughter of Patrick VALLELY & Sarah Ann DALY.

My husband is a descendant of James VALLELY/VELLELY/VELLELEY who was Mary Jane’s older brother.

Can any one tell me where Mary Jane is buried? Also the daughter Sarah- where is she buried?

Thank you for reading. I enjoyed reading about T A Mathews & his wife and family. Tough times.

My husband & I live in BELROSE N S W

Gloria VELLELEY