Dakalanta Wildlife Sanctuary on the Eyre Peninsula – wildlife survey

Nirbeeja and I were recently privileged to be involved, as volunteers, in the first ever survey of wildlife undertaken on the Dakalanta Wildlife Sanctuary, one of the properties owned by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC). As many of you would know, we are passionate about our wildlife, but have no relevant academic training and limited experience in ecological field-work. As a result, our involvement in the survey not only gave the AWC an extra couple of helpers, it also gave us some invaluable experience.

Nirbeeja and I were recently privileged to be involved, as volunteers, in the first ever survey of wildlife undertaken on the Dakalanta Wildlife Sanctuary, one of the properties owned by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC). As many of you would know, we are passionate about our wildlife, but have no relevant academic training and limited experience in ecological field-work. As a result, our involvement in the survey not only gave the AWC an extra couple of helpers, it also gave us some invaluable experience.

DAKALANTA’S BACKGROUND

Dakalanta is located on South Australia’s Eyre Peninsula, roughly midway between Elliston and Lock. You could say it’s pretty much in the centre of the Eyre Peninsula.

The property was purchased by the AWC at the same time it acquired the Scotia sanctuary, which we visited a couple of months ago. Not a great deal was known about the wildlife found on the Dakalanta sanctuary, making our involvement in the survey all the more exciting.

The survey took place over two weeks and consisted of setting up 35 different survey sites and monitoring each over three days. Up to ten such sites were in operation at any one time. The survey team, like a well-oiled machine, would dismantle one set of sites then re-locate them to another area of the property, usually on the same day. Surveys were conducted across a range of habitats on Dakalanta to give a good indication of the wildlife on the 13000 hectare property. Bird surveys were also carried out during the fortnight.

Dakalanta was once used for agricultural purposes and as a result a large portion of the property has been cleared. The Drooping She-Oak, a species of Casuarina, was once widespread across the Eyre Peninsula, but was greatly reduced by such land clearing. It was therefore good to learn that, in partnership with the Eyre Peninsula Natural Resource Management Board, the AWC is setting about re-vegetating Dakalanta, focussing especially on restoring Drooping She-Oak habitat. This will not be an overnight project, but the property and its wildlife will reap enormous benefits from this activity for decades to come. One aim of the wildlife survey was to establish an idea of species distribution prior to this re-vegetation.

During the survey, team members camped near the grounds of the old Dakalanta Homestead, now in serious disrepair and off-limits for visitors and ‘explorers’ alike. Nonetheless, it was interesting to wander around the homestead grounds and see the ruins of what was once a hive of agricultural activity. The open land near the campsite gave wonderful views of sunrises and sunsets, and the glow they cast upon the ruined station buildings.

Our inventive AWC field ecologists set up a drop-dunny for the survey team, under a large eucalypt near(ish) to the campsite. The ‘throne’, in open air, offered panoramic views to the east and prime viewing of the sunrise, though by the end of the survey the aroma of a dead sheep underneath the tree threatened to overwhelm any heavenly views. Anyway, one particularly beautiful sunrise, viewed from these ‘facilities’ sent me sprinting back to our camper trailer for my camera. Contrary to what you may hear from any so-called witnesses, I didn’t have my trousers around my ankles as I made my dash.

Apart from the ruined buildings, the legacy of the earlier agricultural activity is still evident in the heavily cleared areas near the homestead and widespread weed infestation, notably White Horehound and Star Thistle, both of which drove us all crazy in our constant battle to keep their seeds out of socks and clothes. Many of these weeds are opportunistic, that is, they take advantage of cleared or disturbed ground. It is hoped that once the re-vegetation gathers pace the weeds will be out-competed.

The southern part of Dakalanta was most heavily cleared for agriculture, and this is where the re-vegetation will be focussed. Indeed, some re-vegetation is already evident there, as the removal as introduced grazing species has allowed some young She-Oaks and Native Pines to prosper.

The northern half of the property was less damaged by grazing, and consists more of sandy Mallee country and open woodlands.

The one wildlife species that was confirmed on Dakalanta prior to the survey was the Southern Hairy Nosed Wombat. And we can attest to their presence, as their burrows were widespread across the property. Dakalanta is no place to go wandering at night without a torch, unless you know a good orthopaedic surgeon!

Unlike their Northern cousins, the Southern Hairy Nosed Wombat is not regarded as nationally endangered. However, many populations away from the Eyre Peninsula are infected with a serious form of the mange, making the conservation of suitable habitat and healthy wombats, such as on Dakalanta, all the more important. I have the feeling that Dakalanta’s role in the survival of the Southern Hairy Nosed Wombat will become more prominent with time. Dakalanta also forms part of a band of conservation reserves across the centre of the Eyre Peninsula providing a large area of safe habitat for the wombat.

Surprisingly, apart from one possible sighting from a car, we didn’t see any of the wombats during our stay, although we did hear them crashing about and snorting at night. We were usually simply too tired to go spot-lighting for them at night, when they are active.

THE SURVEY

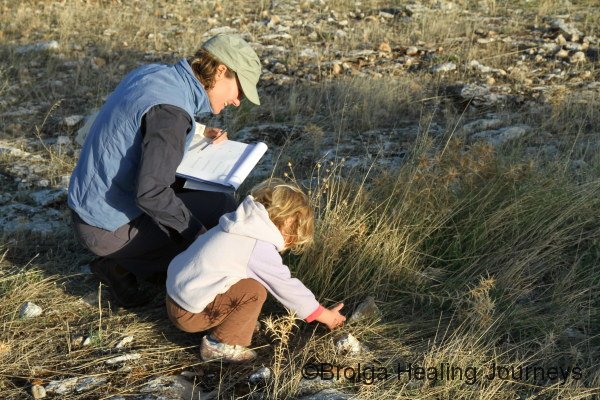

The survey design was overseen by Dr Matt Hayward, AWC’s Regional Ecologist, who was present with his family for the first few days of the survey. We enjoyed their company and were amazed to see Matt’s two daughters, all of three and five years of age, looking every bit the junior ecologists in the field.

The on-the-ground management of the survey was conducted by Keith Bellchambers and Felicity L’Hotellier (Flic), two of the AWC’s Field Ecologists. They were tireless and inspiring, and had the unenviable job of running the survey at the same time as keeping a bunch of volunteers gainfully occupied and out of mischief. It was largely through their efforts that the survey ran so smoothly and proved so successful. They also did a mighty job keeping spirits high as the team laboured away at yet another rocky site to install the survey equipment.

Apart from Nirbeeja and me, the other volunteers on the survey were Katja, Rob, Anne and Margarita, along with AWC Interns Chantelle and Cameron.

Each survey site consisted of two large Y-shaped trapping areas. The lines of the “Ys” consisted of low plastic fence-lines, known as drift-fences. In the centre of each Y, and at its three outer points, were pit-traps – large buckets – while along each side of the arms of the Y were funnel traps. Clear as mud?! Anyway, these are conventional wildlife surveying techniques, and the purpose of the drift-fence is to channel small mammals and reptiles to the pit-traps or funnel traps, where they either fall in, to be later indentified and recorded by the survey team, before release, or wander into the mesh of the funnel to be caught. The pit-traps and funnel traps were checked each morning and afternoon for three days for each site. So, each site has two such Ys, with each arm of the Y around ten metres in length. The drift-fences were lengths of soft plastic sheeting, and to give them stability, trenches were dug along their lengths, and long metal pegs driven in along alternate sides of the plastic.

That also sounded pretty easy, until we discovered that most of the sites were in limestone country – where an inch or two of top-soil basically hid a limestone shelf, or large boulders, underneath. As a result, “installing” the trenches for the drift-fences often consisted of attempting to hack our way through limestone with a mattock! Once that was done, we then had the challenge of hammering in the metal pegs to support the fence. All round the site you would hear “bang, bang, bang, TINK…..expletive” (where tink is the sound of metal hitting rock), to be repeated until a rare gap in the rock was found, or the person gave up and used rocks to support the fence.

Now don’t get me wrong, this was actually a lot of fun and the team shared plenty of laughs. We were also very fit by the end of the survey, though there were days when we were all too exhausted to lift a finger by day’s end.

Along with the two Y-shaped trapping configurations at each site, we installed twenty Elliot traps, small metal cages containing an irresistible peanut-butter-and-oats-bait to entice a creature inside, whereupon they triggered a door, trapping them inside. Two larger cage traps, working along the same lines, were installed at each site in the hope of capturing larger mammals.

Lest I be accused of exaggeration, I should point out that around one quarter of the survey sites were in Mallee country, where the ground was very sandy. These were the favourites of one and all, because installing trenches and pegs were comparatively effortless and, we were to learn, there was more wildlife at these sites (more on that later).

Setting up the sites was only one part of the fun; getting to them was another. Dakalanta does not have much in the way of roadworks. The few tracks on the property consist mainly of limestone rocks – some smooth, some not – linked by small patches of earth. As a result, travel along these tracks was a little bumpy, and certainly slow. Moreover, many of the survey sites were not reached by any such tracks, but could only be reached by bush-bashing. The vehicles would weave their way slowly through the Mallee trees or around and across the rocks, then we’d all jump out to search for the clearest path through the next section of bush. This was quite an adventure, though time-consuming!

It was a busy two weeks, setting up 35 sites, checking them each morning and afternoon for three days, then dismantling each site. The work kept us busy from sunrise to sunset, though I must admit that on a couple of occasions we volunteers escaped for a few hours to the coastal town of Elliston for a shower, coffee and fix of civilisation.

But survey work comes with rewards, and the rewards at Dakalanta were in the form of its wildlife.

DAKALANTA’S WILDLIFE

Before the survey, only the Southern Hairy Nosed Wombat was confirmed on Dakalanta. The AWC can now add to that ‘list’ around two dozen reptile species, close to sixty bird species, and three marsupial species.

THE MARSUPIALS

Not surprisingly, the Western Grey Kangaroo was seen regularly on the property. However, what came as an absolute thrill to us was the capture of some Little Long Tailed Dunnarts and Western Pygmy Possums.

The Dunnarts are small, carnivorous marsupials, with large eyes in keeping with their nocturnal nature. A number of these were caught in the pit-traps to be measured, recorded and returned back to the wild. With so many feral mice on the property and with them often caught in the traps, it was exciting to find a small native mammal instead.

The Dunnarts were cute, but nothing prepared us for the beauty of the Western Pygmy Possums. There can’t be a more exquisite little creature on the planet. I was fortunate to find the first Pygmy Possum on the survey. I looked into the bottom of the pit-trap during the morning check, and there lay a tiny little thing, all curled up with an equally curled little tail. I called to Keith, saying I had a small mammal but it wasn’t a mouse. And yes- indeed, it was our first Western Pygmy Possum, a tiny little juvenile male probably not long independent from its mother. It was a cool morning, and this little fellow had gone into a torpor-like state, which these possums are known to do to cope with the cold. The sight of this fragile, beautiful little creature curled up in Keith’s hand was one we will treasure always. Nirbeeja had tears of joy, I was beside myself with excitement and Keith was quietly beaming. The team was fortunate to see quite a number more of these possums during the survey, each time a thrill for everyone.

REPTILES

The marsupials were thrilling, but really the staple of the survey was the local reptile population. Around two dozen species were recorded, often in apparently barren areas where it was hard to imagine anything prospering.

The most common species was the Barking Gecko (Nephrurus milii), so-called because when threatened they stand up on all fours and make a barking motion and sound, which is actually more like a squeak, but for their size appears quite intimidating. They are a beautifully marked gecko, and we were interested to see variations in marking within Dakalanta. One survey area housed geckos with an unusual spectacle-like pattern on the back of their neck, which reptile-guru Keith had not previously seen.

Second most common was the beautiful spotted and striped Skink, Ctenotus orientalis. (I should mention that Nirbeeja and I had no idea of the scientific names for reptile species before the survey, but by its end could spiel off the names of many species found on Dakalanta; often the names are longer than the lizards.) No-one tired of seeing this beautiful skink, despite the group’s desire for different species.

There were many other reptiles as well – the Western Stone Gecko (Diplodactylus granariensis), the elegant legless lizard Delma australis, the stunningly marked Crested Dragon (Ctenophorus cristatus), and many variations on skinks, some striped, some with brilliant yellow bellies, and others with tiny vestigial-flaps for legs.

Australia is home to over 370 species of skink and to the uninitiated like Nirbeeja and me the differentiation of species is a bewildering process of counting scales, or of examining the shape of tiny scales in all sorts of places on the reptile. Keith was responsible for indentifying reptiles, and we marveled at the way that he did this, patiently and gently examining each reptile using a hand held magnifier, in gloomy light, then consulting his arcane volumes. Some reptiles took upwards of an hour to identify, and the fact that Keith was able to do this after an exhausting day in the field, and not harm a single creature in the process, was testimony not only to his dedication and professionalism, but also to his care for the animals. (Indeed, the team was proud of its record in safely returning all wildlife caught during the survey to the wild.)

The team also caught several snake species, including the Western Brown Snake, the Peninsula Brown Snake, and the Yellow-Faced Whip Snake in the funnel traps at survey sights. The prospect of getting a bite through the mesh of the funnel was good reason to keep a wary eye when checking these traps each morning and afternoon!

DAKALANTA’S BIRDLIFE

Birdlife was abundant on Dakalanta, even around the old homestead grounds where the survey team was camped. We would regularly see flocks of Australian Ringneck Parrots, the largest numbers Nirbeeja and I had seen, and large flocks of Galahs. Welcome Swallows in the same area did their best to live up to their name, while colourful small birds such as the Striated Pardalote and the Yellow Rumped Thornbill were regular visitors.

Elsewhere on the property, species ranging from Australia’s largest (the Emu) to the smallest (the Weebill) were encountered. Many different honeyeaters were to be found in the Mallee, while flocks of Purple-Crowned Lorikeets went whistling by. We also saw the elusive Mulga Parrot and were blessed, as a group, to see a pair of Banded Lapwings nesting near one of the tracks. So strong is the instinct to protect its eggs, the female came in and sat on her eggs even though the party was close-by. After our first encounter with their nesting site, we detoured around the site on future occasions so as not to disturb the Lapwings.

Nirbeeja and I were thrilled to be involved in the survey at Dakalanta. It was hard work setting up the survey sights, but the rewards of encountering many different wildlife species more than made up for that. We loved being part of a team dedicated to protecting Australia’s wildlife, and to have spent time with so many experts in the field. It was a rare privilege. And the AWC now has a good set of baseline data on which to build in future surveys.

We hope to be involved in future AWC surveys as volunteers. If you love Australian wildlife and would like to make a difference, we would highly recommend supporting the AWC, whether by volunteering or by donation. You can do either by contacting the AWC by email. Their website is: http://australianwildlife.org

Peter

March 2011

The photographs in this post are not for sale for copyright reasons. Any errors in describing wildlife surveying techniques are the author’s!

Hi Peter and Nirbeeja,

Your photos are incredible! I’d almost say they look better than reality! The possum’s faces almost makes me cry it’s so cute. And I see you found the lapwing’s nest in the end – nice job! It was great meeting you at Daka and I hope our paths cross again.

Cheers,

Margarita

Thanks Margarita. It was great meeting you too. See you on another survey!

Cheers

Peter & Nirbeeja

The blue flower is Halgania cyanea and the lilac one is Convolvulus remotus. We are the people doing the re-vegetation at Dakalanta (I think we met briefly)and with a bit of luck we should get a hundred thousand or so she-oaks back there. Unfortunately, to do this we will need to spread around some seriously toxic baits for snails and mice. There is really no alternative as germinating sheoaks are very palatable and off target kills are rare. If you go there next summer, you are likely to be disappointed with our results as sheoaks are almost invisible for the the first year or two. Their survival strategy for summer is to withdraw chlorophyll from their leaves leaving bitter toxins, making them unpalatable to roos and then slowly dying from the top down. Although they may appear dead the underground parts are not and they will re-sprout around June for the first few years. It is only after about five years that you start to see grassy sheoak woodland starting to re-appear. We have been doing this for twenty odd years and never cease to be awed by what nature can do with a bit of help.

yours

Merrick & Marion

Hi Merrick & Marion

Thanks for the plant names. Yes- we did meet when you came in with Rob. Keep up the great work you are doing at Dakalanta.

Regards

Peter & Nirbeeja