Blog 12 – More of the Kimberley, then we cross the border to the NT – October 2009

We finished our adventure along the Kimberley’s famous Gibb River Road feeling a strange mixture of elation and flatness. We were elated to have experienced such a rugged, remote and ancient landscape, surprisingly full of wildlife and beauty. We were also elated and relieved to have survived with car and camper trailer intact. But we both also felt flat. How could anything or anywhere live up to what we had just experienced? How could we rekindle the almost magical quality of that region?

It was with these mixed feelings that we left the dirt and drove up the bitumen highway towards Wyndham, the most northerly major town in the Kimberley. We had expected to drive along river flats and past mangrove swamps, but the region was surprisingly mountainous. This was another reminder to us that Australia is a country of surprises. Wyndham itself is a small place, with two halves separated by several kilometers. The more modern administrative half appears to be the ‘growth’ district, while the older Wyndham Port features most of the town’s historic buildings.

Even with both sections combined, it is still a small place. Its population is uncertain (probably around 500), because Wyndham didn’t participate in the last general census. I learned from the local service station owner (always a reliable source in small towns) that the census forms had been misplaced by the local postal authorities and thus not delivered to households in time for them to participate in the census. Perhaps next time they’ll rely upon the bush telegraph.

Whilst the much younger Kununurra, the other main town in the area, is booming due to the Ord River Scheme and its fortuitous placement on the main tourist drive between Darwin and the Kimberley, Wyndham is a victim of its isolation. Wyndham was once a thriving port town and major transit point into our north west, especially during the gold rush when Halls Creek was the place everyone wanted to reach. With most transport now undertaken by road or plane, Wyndham’s role is less certain. It was pleasing to note that some tourist ventures starting up in the area, and it may well be that its very isolation becomes a selling point.

Indeed, we discovered that the region is rich in history – both Aboriginal and white – and that it has its share of natural wonders. Towering above Wyndham is the imposing Bastion – a sheer outcrop several hundred metres high. A winding road takes you up its side to the Five Rivers Lookout, offering some breathtaking views of the region. The wide Cambridge Gulf is visible into the distance and it serves as the confluence of the Ord, Durack, Pentecost, King and Forrest Rivers. From the lookout, each river appeared to snake its way back into its own region of the Kimberley. From such a vantage point the rivers, the lines of mangrove trees, and the distant ranges, form geometric patterns upon the landscape below. We watched a patch of tiny white specks far below move along the gulf, only to realise that this was a large flock of corellas. Other tiny specks turned into large fishing boats with the help of binoculars.

The view was magnificent, and we would love to return during the height of the wet season to witness these five mighty rivers at their peak.

Near Wyndham we stayed at Parry Creek Farm, a place recommended to us by many bird lovers we’d met during our travels north. The farm itself boasts some waterways and birdlife, but its proximity to the famous Parry Lagoons Nature Reserve is its biggest attraction. However, as we drove towards the farm we experienced a horrible sinking feeling, noticing that a large bushfire had recently swept through the region, affecting a large part of the nature reserve. The farm itself had been spared, and we were relieved to learn that Marglu Billabong, the largest waterhole in the nature reserve, had also been spared. We stayed at the farm for quite a few nights, using it as a base from which to explore the region.

We have some lovely memories of the farm itself. On the first night of our stay the farm offered a camp oven meal which proved to be tasty, wholesome food and one of the best value meals of our travels. A regular visitor to our campsite was a juvenile Brolga, an orphan raised by the farm. We felt for this young bird, now old enough to fly, who wasn’t quite certain of her role either as Brolga or human. Nonetheless, she was a welcome and elegant visitor as she wandered the campground.

Nirbeeja had initially been disappointed at the relative lack of bird-life at the farm, especially since the glossy brochure we had picked up during our travels promised all manner of bird-watching marvels, including regular sightings of the rare Gouldian Finch. The reality, of course, didn’t quite live up to this. But we persisted, heading out each morning to small pools along the mostly dry watercourse, and were rewarded to see several Gouldian Finches in amongst some Long-Tailed Finches. When we reported this back to the office, the owners were almost as thrilled by our sighting as us, because at last they could tell visitors that someone had recently seen a Gouldian Finch there!

And the other memorable event during our stay at the farm was Nirbeeja’s 60th birthday. She didn’t get to see a Gouldian Finch that day (the sighting had come a day early), but we did celebrate with a relaxed meal in the farm’s restaurant.

Bird-watching at the farm may not have lived up to our high expectations, but the Marglu Billabong certainly did. We spent the best part of a day at the bird hide on the shores of the billabong, and saw an abundance of waterbirds, including Brolgas, Jabirus, Plumed Whistling Ducks, Wandering Whistling Ducks, Magpie Geese, Purple Swamphens, Radjah Shelducks, and the Comb-Crested Jacana, an elegant little bird whose long slender toes allow them to walk across the lily pads. We also saw many saltwater crocodiles patrolling the billabong in their quiet, sinister way, gliding almost surreally through the water-lilies. One crocodile swam under the bird hide at one stage, much to the delight/horror of a group of Aboriginal children sharing the bird-hide with us at that time. You will have to trust me when I say that the ear-piercing squeals of these kids provided a whole of body experience.

We travelled one afternoon down the ‘4WD only’ Old Halls Creek Road. This 13km section of track was built during the gold-rush days. The sides of the track were paved with local rock and the centre filled with gravel to make it passable in the wet. The road was used by miners, who had arrived by boat in Wyndham, to push their carts and barrows to the Halls Creek gold fields, many hundreds of kilometres to the south. The paving is still visible along many stretches of the track. We felt pretty adventurous driving along this track in our modern 4WD, and can only marvel at the spirit of those who walked along the track, all their worldly goods in the wheelbarrow they pushed, into an uncertain future. Indeed, many didn’t reach the gold fields of Halls Creek and now lie in lonely graves in the bush beside the track.

We stopped briefly to view two waterholes near the track. The second, named Crocodile Hole, was quite an experience. We arrived, bathed in the golden glow of the late afternoon, and looked out over the apparently peaceful billabong. We both jumped when we realised that all the bumps along the water’s surface that we had taken to be rocks, were in fact the eyes of crocodiles contemplating their evening meals – us!! All we could see were eyes, lots of eyes; their bodies cunningly submerged beneath the water. We unconsciously took several steps back, and to be honest didn’t really linger by that waterhole. But what a memory it is.

There were many other sightseeing and exploring opportunities in the area. Wyndham has its own infamous Prison Boab tree, where Aboriginal prisoners were once held, crammed inside the tree overnight, en route to prison or enforced labour (ie slavery). As with the Prison Boab near Derby, this tree had long been considered a sacred tree by the local Aboriginals, making its use by white men as a prison for those same Aboriginals an abominable act.

Also within that region was a magnificent rock face and overhang containing some old and faded rock art.

We also took another day-trip and drove along Parry Creek Road to Kununurra, an alternative route to the modern highway. Along the way we passed Goose Hill, said to resemble a goose but which, no matter how hard we tried, only looked like a hill to us. Next came Black Rock Pool and Middle Springs, both providing waterholes for wildlife, including butterflies galore, and some pretty scenery. However, the highlight of the drive had to be Ivanhoe Crossing over the Ord River. This was once the original road across the Ord River for travelers to Wyndham, and each year is cut off throughout the wet season, but passable by 4WD in the dry. Well, so they say. It’s quite a long crossing and the river fairly rips across the causeway, in some places around half a metre deep. Many drivers chickened out the day we were there, but your intrepid correspondents took the plunge and made it across in 4WD low-range – and breathed a bloody big sigh of relief on the far side.

We ventured on to Kununurra (more about there later) then circled back to Parry Creek Farm along the highway, detouring a relatively short distance along the Gibb River Road to explore Tier Gorge and the Aboriginal rock art site at Matteo Rock. These beautiful places completed a memorable day’s travel for us.

Eventually leaving Parry Creek Farm, we travelled down to Kununurra and stayed several days in one of its caravan parks. Along the highway we visited the Grotto – a deep waterhole nestled in the rugged ranges along the highway. A steep walk down the cliff takes you to the peaceful waterhole, reputedly between 300 and 400 feet deep. Neither of us felt inclined to test its depth.

Onwards to Kununurra. Now, if Parry Creek Farm had provided us with a soft re-entry into the civilised world, the caravan park and township of Kununurra gave us more of a thump. Not that it was a bad caravan park or town; in fact the caravan park was relatively quiet and quite pretty, situated as it is near the Mirima (Hidden Valley) National Park, and the township of Kununurra is an oasis of green. It was nonetheless a shock to our wilderness-attuned systems, especially being in a bustling town again.

Kununurra has grown noticeably since we first visited in 2002. Thanks to an enormous supply of water nearby in the form of the Argyle Dam, the green lawns and gardens of the town provide quite a contrast to the surrounding rocky hills. Kununurra sits in a thriving agricultural region, and is also a major stopover for tourists travelling from Darwin to the Kimberley. Kununurra also gave us our first taste of “the build-up” towards the wet season, by all accounts taking place earlier this year than is usually the case. That means temperatures in the high 30s all day, scorching sun, high humidity and little respite at night. Give me the dry heat we had experienced in the central Kimberley any day.

I took the opportunity whilst we stayed in Kununurra to explore the Mirima National Park. This beautiful place contains many tall bee-hive shaped sandstone domes, and is often described as a mini Bungle Bungles. The most interesting part of the park, for me, was a climb up to an impressive, head-shaped outcrop that to the Aboriginal people represents the Head-Lice Dreaming. Needless to say I was very respectful at the site because I didn’t want to attract the retribution of the Head Lice spirits. But it was an oppressively hot day on which I walked and the headache I had after that walk reminded me to be more careful to walk in early mornings or late afternoons in this part of the world.

NORTHERN TERRITORY – HERE WE COME

KEEP RIVER NATIONAL PARK & BROLGA DREAMING

After around nineteen months in Western Australia, at times wondering if we’d ever leave, we crossed the border into the Northern Territory. This gave us both a much need lift after our back-to-civilization experience in Kununurra, all the more so when we drove into the beautiful Keep River National Park. Given the extreme weather conditions, there were few people camping in the park, and this is just what we wanted.

We arrived at the Gurrandalng campsite and were immediately in awe of the imposing monolith after which it is named, and which towers above the campground. It had a real presence, revealing different aspects of itself to us as the light changed throughout the day. You can imagine our excitement to learn that Gurrandalng means Brolga Dreaming to the Mirriwoong and Gajirrabeng people. Unfortunately, we didn’t see any Brolgas during our stay, most likely because we were there during the dry season and the waterholes nearby were dry. But the dreaming story is as follows:

In the Dreamtime two Aboriginal people travelled from the sea to this area. They collected grass and bushes, made a large nest and started to jump around and make noises like a Gurrandalng (Brolga). As the country listened they changed into Brolgas. The place is named Gurrandalm – the place of Gurrandalng.

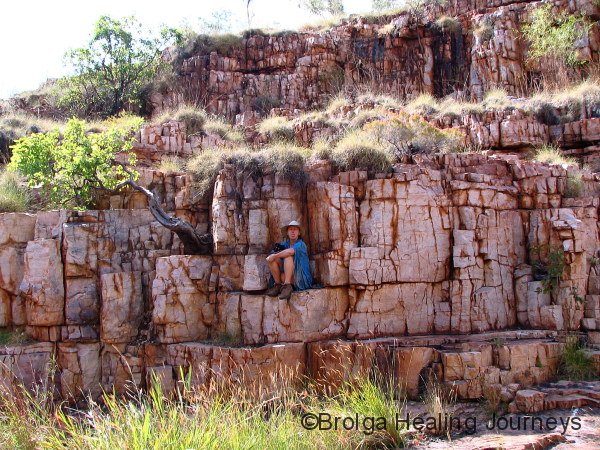

Despite the oppressive conditions (39-40 degrees in the shade during the day, mid 30s overnight, and high humidity throughout), we completed all the walks offered in the national park and enjoyed them all. The park features some spectacular sandstone formations – similar to those in Mirima National Park and the Bungle Bungles – as well as the scenic Keep River gorge and some very interesting Aboriginal occupation and art sites. Unfortunately, one site normally open to the public was closed because of a suspected arson case, but we nevertheless encountered some magnificent rock art, including some Rainbow Serpent paintings many metres in length in a hidden art-site that Nirbeeja chanced to see while we were on a walk, and some interesting space-men-like figures that would have had Erik von Daniken salivating, which we also located in an art site off the usual track. While in the park we also had our first glimpse of the Sandstone Shrike Thrush, an elusive little bird.

In short, Keep River National Park restored our spirits and rekindled our passion to continue our adventures. We hope to return next year at the end of the wet season to see the park in all its glory.

We left the park and headed east. We had planned to travel up to Darwin, Kakadu and Litchfield, but given the heat and humidity decided to travel to Katherine, then south to more welcoming weather.

The journey towards Katherine took us through some magnificent country near Timber Creek and along the course of the Victoria River. We passed through the northern fringes of Gregory National Park and visited the Gregory Tree – a huge Boab marking the place where the explorer Gregory and his party camped from October 1855 to July 1856. Taking into consideration the conditions they must have faced during the northern summer, the uncertainty of food supplies, and virtually no chance of rescue if anything went wrong, these were remarkable people indeed.

We camped in the national park and there met Tony and Yalona, a couple with whom we clicked immediately. Over a few wines we discovered we had much in common and shared many attitudes, to travel, the countryside and life in general. It was a lovely, memorable evening.

NITMIKUK (KATHERINE GORGE)

Our journey eastwards continued, taking us to Katherine, a surprisingly large town which had the dubious honour of possessing the first set of traffic lights we’d encountered in many months. Re-stocked, we went to the nearby Nitmiluk (Katherine Gorge) National Park. We were fortunate not to arrive during the peak tourist season, but there were still plenty of visitors there.

After paying for a campsite and being told where we could and couldn’t go, in a rather offhand, distracted way by a young (European) woman who obviously wished she was anywhere else but at work, we drove in towards camping ground and were aghast to see a collection of caravans, camper trailers and tents all jammed together in the blazing sun. We stopped the car and just sat there stunned.

Just then a Ranger, who must have seen the horrified looks on our faces, walked over to our car. “Would you like a spot with plenty of shade?” he asked. “Yes please” we answered. “And away from all the people” “Oh yes please”, we stammered, almost overwhelmed with gratitude. He pointed us in the direction of a large shady mango tree. We informed him that we had been instructed not to camp there by the lady in the office and he simply replied that we could ignore that advice thanks to him. So we set up camp under the beautiful tree with the area all to ourselves. We had peace and quiet, shade and an abundance of wildlife around the campsite for the duration of our stay. We were regularly visited by Agile Wallabies, Red-collared Lorikeets and Varied Lorikeets. Our friend may have been wearing a Ranger’s uniform but we are convinced he was an angel sent to us from above. Every time we walked from our perfect spot past all the crowded, sun-scorched campers we whispered a quiet word of thanks to him.

Nitmiluk (Katherine Gorge) is famous, and with due reason. It is a stunning place. But it was so hot while we were there I opted out of any bushwalks; a first for me on our adventures. Nirbeeja, not surprisingly, required little convincing not to go walking. By all accounts the temperature on the exposed rocks above the gorges was in the mid 50s. The visitor centre had a piece of rock heated to the temperature on top of the gorge, and it burnt your hand to touch it. (For me it brought back memories of a day spent on a sheep station near Louth in NSW, where the metal rails around the sheep yard were dangerously hot to touch.)

Instead we went on a cruise along the first three gorges of the many that comprise Nitmiluk. The cruise-boat took us to the end of the first gorge. A short walk from there took us to the start of the second, where we joined another boat. At the top of that gorge we repeated the process, and then performed the same boat-hopping exploits on our way back down the gorges.

We thought the second gorge the most stunning, with its 65 metre high cliffs towering above us. The gorge features a large bend and during wet season floods this area of the river becomes a huge whirlpool. The trees along one bank of the bend, which are normally above river level, all lean against the normal direction of river flow. This is dramatic evidence of the wet season whirlpool which reverses the river flow on that side of the gorge. The local Aboriginal people believe that the Rainbow Serpent lives in this part of the gorge and traditionally, pregnant women and recently initiated men were forbidden from approaching that area. When Nitmiluk floods they also believe that it is because the Rainbow Serpent has been angered. It certainly was an awe-inspiring place and one that commanded respect.

On the return part of the cruise we had a delightful swim and visited some interesting art sites. As with Keep River, we vowed to return to Nitmiluk after the wet season and explore the many bush-walks through the park.

WE OF THE NEVER NEVER

Heading south now, we were off to Mataranka, stopping along the way at Cutta Cutta Caves, a limestone cave system. Cutta Cutta means “big mob of stars” in the local Aboriginal language, and the sparkling limestone formations certainly showed why the local Aboriginals named it thus upon first sighting the caves.

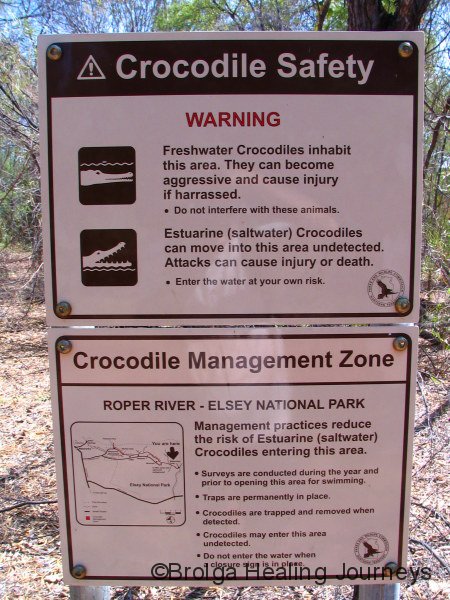

We camped at Elsey National Park near Mataranka, an area famous for its thermal springs. From our campsite we went on a lovely walk to Mataranka Falls, which while not exactly Niagra-like in their magnitude were nonetheless very pretty. We swam in the Roper River near the campground. Well, it was more a case of leaping in, cooling down then bouncing straight back onto the pontoon. Warning signs about crocodiles made us uneasy about extended stays in the river. The signs tried to re-assure visitors that every effort was made to ensure no saltwater crocodiles remained after the wet season, but the wording wasn’t entirely convincing. We had no desire to make the news for all the wrong reasons!

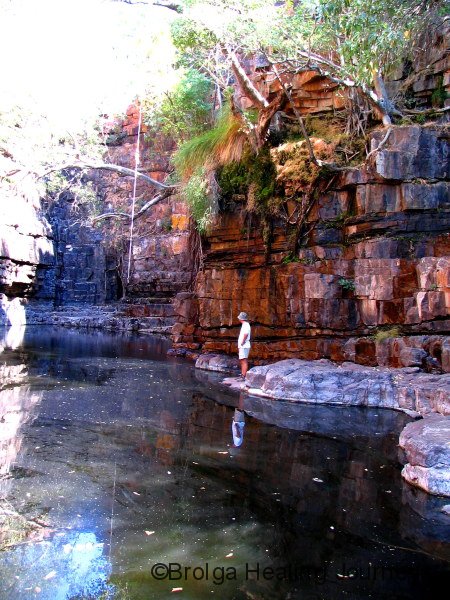

We visited the famous Mataranka Springs. The main spring was well maintained and presented for visitors, with a welcome mix of natural settings and steps to ensure safety, and beautifully clear, tepid water. The only problem was from above; there were literally thousands of Little Brown Flying Foxes pooing everywhere from the overhanging Livistonia palms. This not only made you tread carefully to avoid the green slimy stuff, it also ensured you kept your mouth closed when you looked up. And it left me with suspicions as to what had dissolved in the pool we were soaking in.

We were more impressed with the nearby Rainbow Spring, which feeds the pool in which we bathed. This was quite exceptional. The spring water was crystal clear and gushing up through a hole in the rock more than one metre wide. This outpouring from the spring amounts to 30.5 million litres of water each and every day. It really was something to behold.

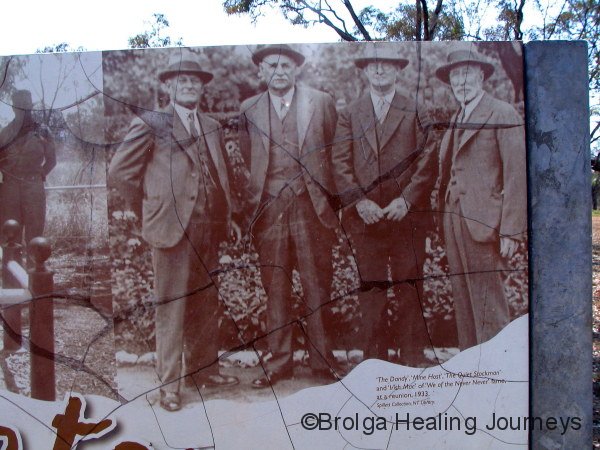

The Mataranka region is also famous as the setting for the well known Australia book “We of the Never Never”, written by Jeannie Gunn in 1908 about her experiences on Elsey Station. Neither of us had read this book, though we had of course heard about it. We managed to secure a copy while in town, admittedly at a fairly steep price from a tourist venue. It was a marvelous book, greatly enriching my experience of the region and gave me a wonderful insight into the difficult lives of early white settlers. We were both amazed at how little the book had dated; like all great writing Gunn made you feel as though you were part of the story and among friends. We visited to site of Elsey Homestead, where the book was based, and also visited the graveyard where most of the characters in the book are buried. Given the poignancy of the writing, this visit was a particularly emotional one for me. We both now count “We of the Never Never” among our most beloved books.

Continuing our odyssey south, we covered around 600kms to arrive in Tennant Creek. We both had some difficulty comprehending such a big day of travel, after months spent covering much shorter distances across, we must admit, far worse roads.

That long day’s travel had one highlight – the Daly Waters Pub. Now there is an Aussie Pub. It was steeped in character and full of characters, both local and visiting. Every available inch of wall and ceiling was covered with some item of memorabilia; hats, licence plates, ID cards, bras. You name it, it was there. We had Barra Burgers for lunch – a huge meal – and a beer, taking in the atmosphere and watching the crowd, and thinking of all the friends we would love to had have there with us to enjoy the atmosphere.

TENNANT CREEK – A PLACE OF ANCIENT CULTURE

We arrived in Tennant Creek for our first re-union in many a long month. Susi Witt, a friend of ours who had worked with me at the Hierophant in Canberra, had recently moved to Tennant Creek to work with the Aboriginal communities there. Susi was looking really well (though probably not so well after a couple of late nights celebrating with us!!) and is enjoying her work there.

Nirbeeja and I had both passed through Tennant Creek many years ago but neither of us had any memories of the place. This time around we found a town working very hard to resolve the many social problems facing outback towns. It is a town with a heart.

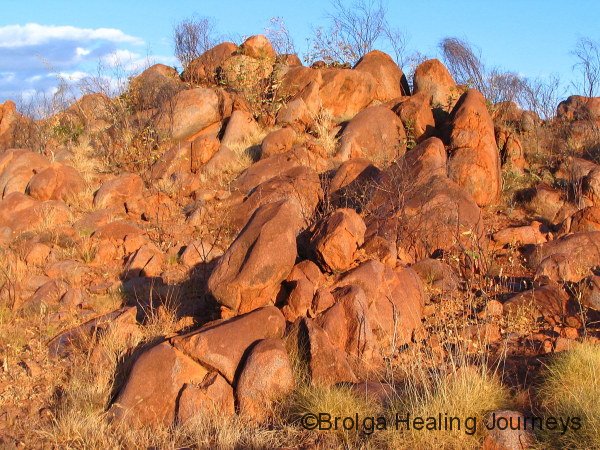

Spending a couple of days there also allowed us to explore some of the interesting places near the town. Most of us have heard about the Devil’s Marbles, but few people, including us, have heard about Kunjarra – also known as the Pebbles, a few kilometers to the north of town. To look at, Kunjarra is a smaller version of the Devil’s Marbles. But one shouldn’t be deceived by appearance, for this is a very powerful women’s place. I trod very carefully and respectfully around the site, careful not to venture into areas off-limits to men. Even so, I experienced a number of ‘shivers down the spine’ moments and at one stage was covered in goose-pimples for several minutes on what was a very hot day. It was one of the most powerful, potent places we have encountered during our travels. The traditional custodians of the site have asked that visitors not camp near the site, and we heard stories of strange and somewhat spooky happenings to people who ignored this advice. Needless to say, we stayed in town at night!

Tennant Creek is making quite an effort to attract visitors. The Old Telegraph Office near the town had been restored and is well worth visiting, as is the Nyinkka Nyunyu Cultural centre in town and the Julalikari Arts centre.

We had dinner with Susi both evenings we were in Tennant Creek. We also had the pleasure of meeting three workmates of Susi’s, all of whom, like Susi, had arrived in town within the past few months. We were greatly impressed by these remarkable young women, all helping in local community, and can’t help wondering if the power of the nearly Women’s site had some bearing on drawing them all to the area.

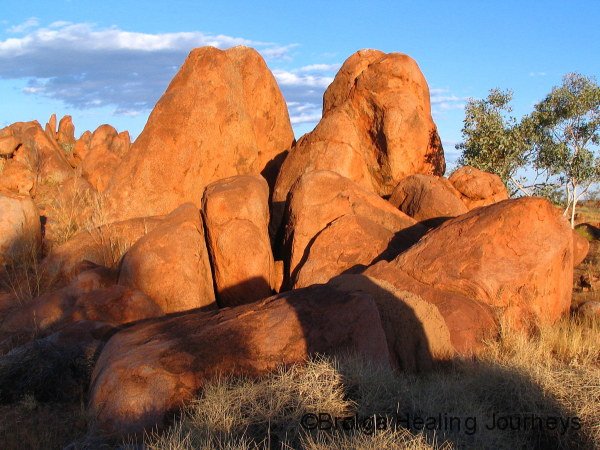

Next stop was Karlu Karlu (better known as the Devil’s Marbles), a famous and beautiful place, and Aboriginal Men’s site. We couldn’t get over the size and scale of the rocks. There are literally thousands of huge boulders seemingly strewn at random around a wide, shallow valley, often stacked in high clusters. Many boulders were as big as a house. At sunrise and sunset they glowed red and orange, a breathtaking sight. Surprisingly, the site didn’t have the same feeling of intense power as Kunjarra, but it was visually more stunning. Perhaps the thousands of tourist visitors, some of whom disrespect the site leaving rubbish and graffiti, has dissipated the power at Karlu Karlu. But Karlu Karlu is definitely a site for Men’s Business, and the shape of some rock formations certainly erased any doubts as to the gender of the place!

Interestingly, Kunjarra and Karlu Karlu are linked by Dreamtime stories, many of which concern travel by Dreamtime beings between the two sites.

The geology of Karlu Karlu is fascinating, telling the tale of erosion across countless millennia. The granite rock from which the Devil’s Marbles are formed was once a single mass of stone. Over millions of years erosion along joint planes produced angular slabs of rocks, which gradually became rounded by wind and water into the marbles we see today. Some of the marbles appear to have cracked in half relatively recently, giving the impression of a ball sliced in two, while others similarly cracked but older show rounding off around the edges. These apparently dramatic breaks are the result of water finding its way into cracks in the boulders, speeding up the process of erosion.

WYCLIFFE WELL – WE ENTER THE TWILIGHT ZONE

We continued our journey southwards, travelling through Wauchope (“When do we get to Wauchope?” asked Nirbeeja, to which I replied “We drove past it a while back”; obviously she had blinked at the wrong time), to our next overnight stop at Wycliffe Well.

Wycliffe Well offered a cultural experience of an altogether different kind. For Wycliffe Well is the self-proclaimed UFO Centre of Australia. The combined caravan park/service station/Chinese restaurant/pub/supermarket of Wycliffe Well feature an amazing, dare I say out of this world, collection of UFO and ET-based murals, and life-sized figures, not to mention are few bizarre ring-ins like Elvis and the Phantom. It is real wonderland. The walls inside the shop and restaurant are plastered with newspaper and magazine articles about UFO sightings, many from the Wycliffe Well region.

Interestingly, the connection with UFOs goes back many decades. There were many reports of strange objects in the sky by soldiers stationed there during the Second World War. UFOs are still seen regularly, though the large range of imported beer on sale at the bar may go some way to explaining this. Others suggest a link with the top secret defence bases relatively nearby at Pine Gap and the Harts Range. It is an intriguing place that is partly theme park and partly serious.

The owner of Wycliffe Well has, by all accounts, seen many unusual objects in the sky, though we found the locals strangely reticent to talk about the UFO phenomenon. Given the amount of work they had put into their exhibits we are puzzled as to why that is the case. Possibly they are tired of being ridiculed by people. Anyway, despite Nirbeeja and my best efforts of sky-gazing, including being primed with sufficient beverages from the bar, we are unable to report any sightings of note to add to the local legend.

A TOWN LIKE ALICE

Having avoided alien abduction in Wycliffe Well, we continued our southward journey. Next destination Alice Springs. We were both tremendously excited about this, not only looking forward to exploring the iconic Red Centre of Australia, but also greatly anticipating our re-union with Claire and Terry, fellow travellers whom we had met crossing the Nullarbor Plain at the start of 2008. We had become great mates with them, travelling together in WA’s South West for many weeks, before parting ways in Busselton some 18 months ago. Claire and Terry were now working in Alice Springs, having secured a two year working visa to help them to escape England’s lousy weather and come to the promised land. For a couple of Poms they aren’t bad company!

And yes, it has been fantastic to catch up with them. They have generously allowed us to stay with them in Alice Springs, giving us a great base from which to explore the broader region. After only a short while, we all remarked that it felt as though we had never been away from each other. This for all of us was a sign of being with true friends. Since arriving, Nirbeeja and I have spent as much time exploring with them as their work would allow, and have also gone off on extended trips by ourselves.

We were both amazed at how much there is to do in Alice Springs, let alone the wider region. The annual Alice Springs Desert Festival was in full swing on our arrival, and we attended a number of events, including a rock concert featuring indigenous bands from surrounding desert communities, an African-style choir performing at the magnificent Trephina Gorge in the Eastern MacDonnell Ranges, the most beautiful natural amphitheatre imaginable, and the annual Desert Mob art exhibition featuring works from all the surrounding communities. I should explain that in this region, where distances matter little, ‘surrounding’ actually encompasses communities 1500km away. The art was literally mind-blowing. It was amazing stuff, and by the end of the exhibition we both felt that our visual cortexes had been scrambled, re-assembled, re-programmed and generally given a good working over. The colour, patterns, intricacy and above all the energy of the works were something to behold. Being a lover of Aboriginal art, I twice visited the exhibition and also ventured into a number of the large commercial galleries in town. Seeing such magnificent art brought back great memories for me, for it was during my first visit to Alice Springs some twenty years ago that I had experienced the power and beauty of Aboriginal art for the first time. I was thrilled to re-experience the same sense of awe and wonderment this time, despite having seen a lot of Aboriginal art during the intervening years.

We also visited the Desert Park on the western fringe of town, a large reserve show-casing the local flora and fauna. This park extends over many acres and we were only able to explore a small part of it during our visit, partly because the weather was so hot we’d have fried spending more time wandering around outside. We loved what we saw, and thoroughly enjoyed a raptor display, where a series of trained raptors (birds of prey) ‘performed’ fly-bys and feeding displays with uncanny timing. They performed like clock-work; such is the motivation of a free feed to a wild and intelligent animal.

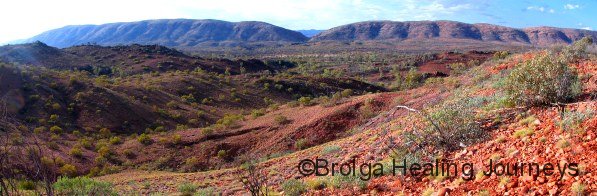

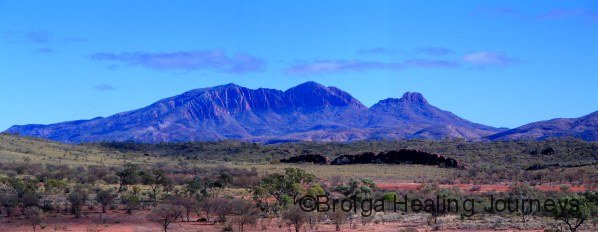

Nirbeeja and I took a day-trip out to explore the Eastern MacDonnell Ranges. The Eastern MacDonnells are smaller and less well known than their Western counterparts, but nonetheless feature some spectacular ranges, outcrops, gorges, gaps and ancient Aboriginal sites. We were both surprised at the magnitude of the MacDonnell Ranges. The Eastern Ranges extend more than 100kms from Alice Springs, while the Western Ranges continue well over 170km from Alice. Both ranges feature row upon row of parallel mountains. They are simply magnificent. In the distant past they surpassed the Himalayas in scale, and while erosion has greatly reduced their height they are still something to behold.

To the east we visited Emily and Jesse Gaps, Corroboree Rock, Trephina Gorge, Ross River Resort and N’Dhala Gorge. It was a big day to say the least. We returned with Terry some days later (Claire was sleeping at the time before her next night-shift at the hospital) to visit the Arltunga historic site, once the largest settlement in Australia’s centre during the halcyon days of the gold rush. Much restoration has been done there to showcase the hard lives our early prospectors.

Claire and Terry took us out camping in their beloved bus Tilly to their favourite spot in the Western MacDonnells – a car park. We must admit to being a little horrified at the prospect of camping in a car park. We had visions of chilling out in the car park of a suburban shopping centre! We needn’t have worried. This ‘car park’ was set high on a hill in the centre of the ranges, about 80km west of Alice. The views in all directions were magnificent, especially at sunset. The next day we walked through the enormous Ormiston Gorge, and visited Glen Helen Gorge and Ellery Big Hole. The Western MacDonnell Ranges feature some famous landmarks, such as Simpson’s Gap, Standley Chasm, Serpentine Gorge and Ormiston Gorge. But they tell only a small part of the story, because the 170km or so of mountain ranges linking these places are really what makes the MacDonnells so special. Nirbeeja and I have since returned to the Western MacDonnells (indeed, this is being written there now) and have taken as much pleasure in sitting at a little-known campsite, with no-one else around, watching the changing light on the surrounding hills and listening to the bird-life, as we have in seeing the famous landmarks to tick them off the list of must-see tourist places. Climbing any hill in the MacDonnell Ranges at sunrise or sunset reveals a setting of timeless splendour.

As many of you would know, we had arranged a flying visit to Canberra

in early October to see family and friends. We therefore had a couple of weeks to spare before our flight, so what would we do? Well, the answer was obvious really, we’d go to Uluru, Kata Tjuta and Watarrka (home of King’s Canyon).

WE VISIT AUSTRALIA’S SPIRITUAL HEART – THE LAND OF THE DESERT OAK

The weather during our first week in the centre had been unrelentingly hot and dry. Every time we mentioned travelling to Uluru, Kata Tjuta and Watarrka we were strongly advised to do all our walking first thing in the morning to avoid the heat. As luck would have it, the cool change to end all cool changes passed through the centre on the very day we drove from Alice Springs to Uluru. Wild winds buffeted our car and trailer all along the highway, for the second half of the journey meeting us head on and making a complete mess of our fuel economy.

We watched huge columns of orange-red dust rise up to either side of the highway as enormous Willy Willies appeared to leap up in anger out of the desert. Some we drove straight through to be blasted by sand and the debris of vegetation. We saw bushes large and small being tossed across the road and along the desert dunes.

You may well know that day; it was the day that the whole eastern seaboard was cloaked in a dust storm, Sydney Harbour Bridge barely visible and Sydney’s airport closed. Well, we know where all that dust came from because we were attempting to drive through it while it happened!

But there is a silver lining to every dust storm, because the front abated, at least out here in the centre, and the weather cooled dramatically for the next week or so.

Mt Conner, the first of the major landmarks between Alice and Uluru, had been barely visible as we drove in, but by the time we reached Yulara the wind had largely abated and the dust settled.

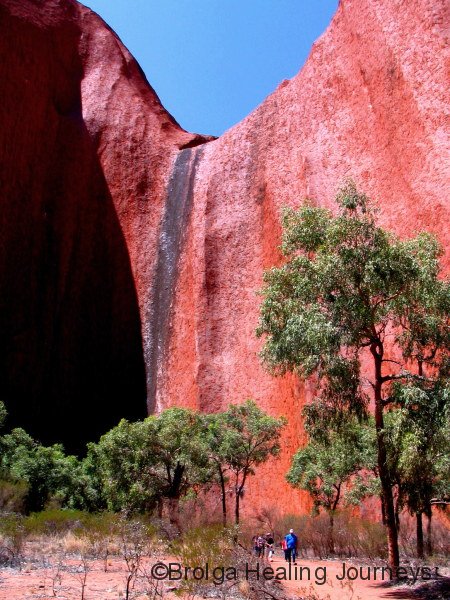

What can we say or show about Uluru that hasn’t already been written or seen? The image of Uluru is etched deeply into the mind of all Australians as our most beloved place. No matter whether you have visited or not, you have seen the image thousands of times. Yet there is no preparing for the very presence of Uluru, as it rises before you out of the desert, towering some 348 metres above its surrounds. Uluru first becomes visible some 30 or more kilometers away, and the sight is thrilling. Nirbeeja, who had never seen Uluru before, was overcome with emotion upon her first glimpse, and she was barely able to tear her gaze from Uluru for the entirety of our stay.

Uluru has an ancient omnipresence, its timelessness inspires wonder, it feels both nurturing and commanding. It means different things to each and every one of us but all who visit there are touched by it in some way. We went on a walk with a Ranger along the Mala (Rufous Hare Wallaby) Dreaming route at Uluru’s base, and at the start of the walk he asked us what Uluru meant to us. Nirbeeja probably summed up Uluru most succinctly when she answered that she considered Uluru to be Australia’s Spiritual Heart. The Ranger simply smiled, nodded and said ‘perfect’.

To the Anangu, as the local people call themselves, Uluru represents not one place or being, but the outcome of many creation stories which are not necessarily connected. We were fortunate to learn about three such stories while we were there: the Mala (Wallaby) story, concerning one area of the rock; the story of Kuniya, the woma python woman and her encounters with Liru, the poisonous snakes, near another site; and Itjaritjari, the marsupial mole, at a further site. The various features on the rock at these sites were explained by these stories and greatly enhanced our experience and understanding of Uluru. Many other stories explain the creation of different aspects of Uluru, but a number of these are withheld from the general public and those sites closed from access or photography.

We were sad to learn that Mala (the Rufous Hare Wallaby) is no longer found wild on the Australian mainland, mainly due to feral predators. Fortunately, some remnant populations of this beautiful little creature have survived on a few islands around the Australian coastline, which have remained feral cat and fox free. Some efforts are underway near Uluru to return Mala to the area in a feral-proof enclosure that is kept off limits to the public. We can only dream of the day when Mala, so prominent in the law and mythology of Uluru, can once more wander free in the area.

We walked around the base of Uluru in perfect conditions, cool and breezy. The base itself is 9.4 km around, but the path drifts away from the rock in some places (to avoid areas closed to the public), so the whole walk is probably closer to 12km. This gave us a great appreciation of the magnitude of Uluru. We chose not to climb Uluru, to honour the request of the traditional custodians. You may have seen recent news reports about the damage caused to Uluru by climbing, including the fact that many people use the top of Uluru as a public toilet. A Ranger mentioned to us that the permanent waterholes at various points around the base of Uluru have been poisoned by the sewerage and other human waste (eg cameras, hats, batteries, food wrappings) that wash off the side of the rock and collect at these points after rainfall. Nirbeeja and I firmly believe that climbing Uluru should be stopped for cultural reasons, but surely now there are also strong environmental and health reasons for closing the climb.

As the Rangers and traditional owners of Uluru stress, there is so much to do there and learn about, that once you understand more about Uluru and its importance, you really don’t feel like climbing anymore. The Uluru Cultural Centre provides a huge range of information about Uluru, both from the traditional perspective of the Anangu and from the western geological viewpoint. Interestingly, the centre contains a huge collection of letters from visitors over the years, called the Sorry Book. These letters are from people who had taken home some rock from Uluru, or who had climbed the rock, or visited or photographed sacred places. Many of these letters were from people whose conscience had simply forced them to return the rock to its rightful place, or who felt the need to confess their wrongdoing, while others had returned their souvenirs because their luck, they perceived, had taken a decided turn for the worse since they had stolen the rock from Uluru. The letters made fascinating reading, and had come from all parts of the globe.

For many people Uluru means climbing the rock and sunset photos, and not a great deal more, especially those who are restricted to a very short visit. The Rangers see education as being the best way to change attitudes to Uluru. A couple of decades ago over 90% of visitors climbed the rock; now only around 40% choose to do so. So something is working. Admittedly, sunset at Uluru is spectacular, watching the transition of colours as the sun fades, and contemplating the countless sunsets at that very place. A huge crowd builds up each afternoon in anticipation of the sunset, with cars lined up at a viewing area at least a kilometre long, with another whole area set aside for the thirty or so coaches full of tourists.

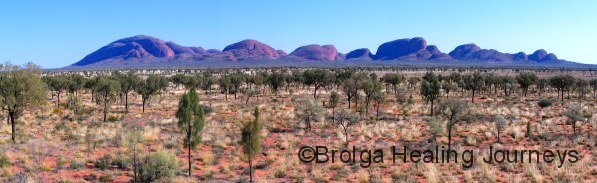

Kata Tjuta (‘Many Heads’) may be some 30km as the crow flies from Uluru, but it is clearly visible in the distance. You don’t really appreciate the scale of Kata Tjuta until you draw nearby. The tallest dome (Mt Olga) is 546 metres above the surrounding land ie around 200 metres taller than Uluru. It is an awesome place. There are 36 domes in all, with the whole group covering around 35 square kilometers. Unlike Uluru, which is composed of sandstone made of uniformly small grains of sand, Kata Tjuta is composed of conglomerate rock, all shapes and sizes of rock, pebbles and sand crushed together. This harder mixture has offered greater resistance to erosion than the sandstone of Uluru, explaining (at least in Western geological terms) why some of the domes are higher.

Traditionally, Kata Tjuta is a powerful Men’s Site, managed only by initiated men, and there are no stories which can be told to the casual visitor. Kata Tjuta certainly feels a very powerful place, somewhat harsh and unforgiving, a place where you tread respectfully, cautiously and warily and don’t overstay your welcome!

Nonetheless, we thoroughly enjoyed exploring Kata Tjuta, walking up the Olga Gorge late in the afternoon, dwarfed by the towering cliffs on either side, and watching a spectacular sunset on some of the domes. We also completed to Valley of the Winds Walk, which fully lived up to its name as well as treating us to some beautiful country.

The iconic landforms of the centre attract most commentary, and rightly so, but the vegetation is also quite stunning. Principle among this is the stately and hardy Desert Oak, widespread through the central desert region. This tree really epitomized the area for me – resilience, age, grace and elegance. It is a beautiful tree. Young Desert Oaks start off as a spiky clump of branches, too prickly to be grazed by kangaroos or rabbits, then grow to become a bushy looking poplar-shaped tree. Eventually, perhaps decades later, once the deep growing tap root has reached subterranean water, the tree transforms into its wide branching adult form. There is no sight quite so beautiful as a stand of Desert Oaks in the late afternoon, with spinifex and red sand at their feet, and Uluru or Kata Tjuta looming in the background.

Our next stop was Watarrka National Park, home to Kings Canyon and the George Gill Range, a place neither of us had previously visited. The road from Yulara to Watarrka is now sealed, making for a straightforward trip through some lovely country, surprisingly hilly in places. Whole stretches of sublime Desert Oak forest made to trip a joy. With school holidays underway there was plenty of traffic to keep us company on the road.

Watarrka is the Luritja name for the umbrella bush which grows in the region. This plant, a member of the Acacia family, was of considerable value to the local people.

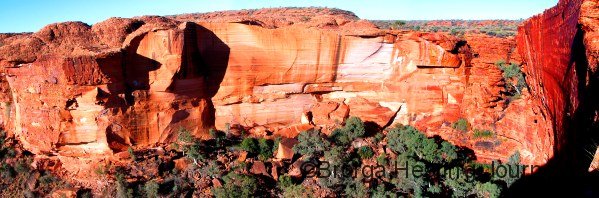

Kings Canyon itself was know to the Luritja as Watarrka Karru (Karru meaning creek), and was a very special place of ceremony for them. This was on a native cat (Quoll) dreaming track and in the Dreaming, native cat men called kuningka travelled from the southwest along this creek and had important ceremonies at the foot of the waterfall in the canyon. The Aboriginal people were highly respectful of the area, to the point not breaking plants or collecting food there. Kings Canyon has a feeling of profound peace to it. The canyon itself is enormous, with sheer cliff walls rising up to 150 metres from the creek below.

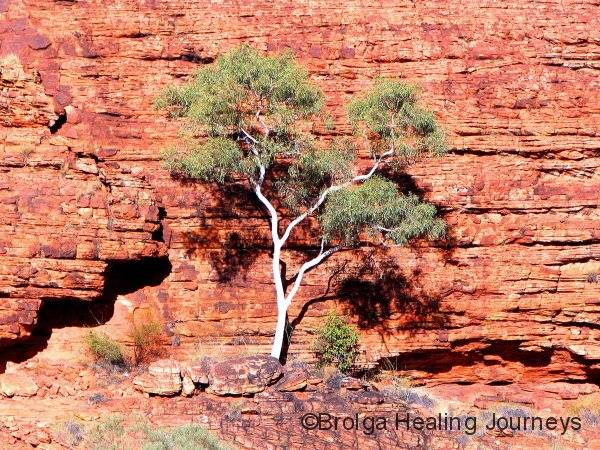

Watarrka is home to 17 remnant plant species which have survived since ancient times in the moist recesses of the canyon. These species include the cycad, a palm which can survive for hundreds of years, which prospers around sheltered, permanent waterholes throughout Australia’s centre. The permanent water of Kings Canyon is also a haven to birdlife.

The Kings Canyon rim walk was particularly interesting, once you had recovered from the initial part of the track which takes you straight up the side of the canyon. It certainly blew any cobwebs out of the system! The route then passed around the cliff-face, through an area of sandstone domes known as the Lost City and through a narrow gorge known as the Garden of Eden, above the main canyon. The whole walk was spectacular and gave us a better appreciation for the enormous scale of the canyon.

We also enjoyed a walk to the less spectacular, but nonetheless very pretty, Kathleen Springs, further along the George Gill Range. The beautiful small waterhole at the end of the walk is still believed by the Luritja people to be home to the Rainbow Serpent. It was a place thriving with life.

Watarrka held another surprise for us. Nirbeeja had a chance meeting with Sindhu, a fellow former Swami from the Satyananda Ashram, whom she had not seen in well over a decade. We had a wonderful evening with Sindu catching up on each other’s news, Nirbeeja and Sindhu in particular having a lovely time reminiscing about their days in the ashram.

Leaving Watarrka, we chose to travel the Mereenie Loop road on our way around to the Western MacDonnell Range. This road passes through Aboriginal land and you require a permit to gain access to the road. We spoke to several people about the condition of the Mereenie Loop; some said it was terrible and others said it was fine (“except for a few corrugations and a few potholes”). We thought, oh well, let’s give it a go. It was pretty rough to say the least! Some stretches weren’t too bad but overall we thought it rougher than the Gibb River Road. Most of the road consisted of severe rocky corrugations. However, the Mereenie loop did take us through some beautiful country, including to Gosse Bluff, a 140 million year old comet impact crater.

We drove in to the centre of Gosse Bluff, an area of spiritual significance to the local Aboriginal people whose Dreamtime story, we were interested to note, also concerned ancient astronomical events.

Their story is as follows:

In the Dreamtime, a large group of women danced across the sky, as the Milky Way. They were stars taking the form of women. During this ceremonial dance of the Milky Way Women, a mother put her baby aside, resting in his turna, a wooden baby carrier. The turna toppled over the edge of the dancing area and fell to the earth. The baby fell down into the ground and his turna fell hard on top of him. At the place where it crashed into the ground, rocks were forced up from underneath, forming the circular walls of Tnorala (Gosse Bluff).

The Milky Way baby was covered with sand and hidden from view. The mother as the Evening Star and the father as the Morning Star, are still looking for their missing baby.

The area had other fascinating Dreamtime stories which were shared at an information shelter.

We left Gosse Bluff and continued along the Mereenie Loop, breathing a sigh a relief when the dirt gave way to bitumen, which we later discovered continued all the way around through the MacDonnell Ranges to Alice Springs. A high lookout at Tylers Pass provided a fantastic view of Gosse Bluff in the distance and of the surrounding western fringes of the MacDonnell Ranges. It was a mighty view and the equal of any we had seen.

Some time later, feeling adventurous (and just a little rebellious) we headed off the main road up a rough track into the bush, we believe on a cattle station, and set up camp for the night. After many nights crammed in with the masses at Yulara and Kings Canyon resorts, we thoroughly welcomed a chance to be all alone.

The following morning we headed in to the far end of the West MacDonnell National Park, visiting Redbank Gorge and staying at the lovely, nearby Woodlands campground. This was a national park campground at its best, featuring a beautiful natural setting, with large campsites and plenty of space between them, so that you felt as if you had the place all to yourself. We stayed a couple of nights, allowing me to explore the surrounding countryside while Nirbeeja relaxed at the camp and indulged in some serious bird-watching.

The highlight of my explorations was climbing to the top of Mt Sonder. To the local people this is Rwetyepme (pronounced Roo-choop-ma), a significant Euro, or Hill Kangaroo, Dreaming site. It was one of the longer and tougher walks I have completed on our adventures, consisting of an 8km trek up the range to the top of Mt Sonder, the Northern Territory’s fourth highest peak, followed by 8km back down to the bottom. And if that wasn’t long enough, I chose a day with howling winds. Near the top of Mt Sonder the winds were unbelievable. I had to hold my hat on with both hands and several times was knocked sideways by strong gusts. The wind had stirred up a lot of dust in the valleys below, but the views from the top were still superb. Hills that I had struggled up along the route appeared no more than anthills from the peak of Rewtyepme!

While I was contending with the elements on Rwetyepme, Nirbeeja had her own battles with the wind back at our campsite. The wind was threatening to blow our camper trailer to pieces, and I returned from my walk to find that a rather harried looking Nirbeeja had somehow managed to pull down a couple of sections of canvas while I was away, in order to protect them.

The following day the wind had settled into perfect, cool, clear sunny conditions. We pulled up camp and headed east, planning to stay at the camp-ground at Ormiston Gorge, But one look there revealed campsites cramped closely together, and we had had enough of being human sardines at Yulara and King’s Canyon. So we headed further east through the ranges.

We visited the Ochre pits, a steep sided erosion gully used for thousands of years by the local people to obtain ochre for their ceremonies. The gully supplied a rainbow-like range of colours and was well worth the visit.

Next, we drove along a rough 4WD track to the ruins of Serpentine Chalet, a popular tourist stopover in the 1960s, but now no more than foundations. However, bush camping is allowed along this track and we found a perfect campsite. You beauty!! It was sheltered, flat, secluded, and surrounded by gorgeous hills. And believe it or not, free. We gladly set up camp here and have been here now for three days. It has been a lovely base from which to explore.

Our past few campsites have given further evidence to our bizarre theory that the cheaper the campsite, the better it is. At Yulara and Kings Canyon we paid exorbitant amounts to be crowded in with family after family of either drunken adults or screaming kids, in fact sometimes both, and to put up with grimy, overloaded amenities. Such is the lot of visiting such famous places. By contrast, our past three sites have been out in the bush in pristine surroundings, admittedly with few amenities, but given our virtual self-sufficiency they have all we need.

In general, we have been really impressed by the national parks in the Northern Territory. The parks have been well cared for, camping areas and facilities have been simple yet beautiful and visitor information comprehensive and sensitive both to the western and Aboriginal viewpoints. Keep up the good work, is all we can say!

Yesterday we drove to the nearby Serpentine Gorge, which was my favourite gorge in the region when I first visited 20 years ago, and I am pleased to say it remains so after our return. The gorge is aptly named, spectacularly snaking its way northward from a waterhole on the southern side of the range. High cliffs seem to crowd in on the edges of the creek, creating the gorge’s well defined serpent shape. So long as your heart and legs can stand the strain, a steep track to a lookout at the top of the cliffs reveals the full splendour of this magnificent gorge. The Aboriginal people were fearful of this gorge and drank from the waterhole only in desperation, never swimming in it, nor did they venture up the gorge. They remain fearful of the gorge to this day and rarely visit it. For them, the waterhole is home to a fearsome Rainbow Serpent, and the snaking gorge obvious evidence of its presence.

This morning we walked the 8km round trip to Inalanga Pass, a steep cutting through the range. The deep gorge is home to some huge cycads, nestled among the huge boulders which line the base of the sheer deep red cliffs. The pass once marked the boundary between two tribes and would only be crossed once permission had been gained.

Today is our last day (for now at least) at this beautiful campsite. We return tomorrow to Alice Springs, where we will help Claire to celebrate her birthday, then prepare for our flight to Canberra.

Hoping to see many of you soon.

Till next time.

Peter Hammond & Nirbeeja Saraswati

4 October 2009