Blog 11 – We return to the Kimberley, land of the Wandjina and the Boab – August 2009

FIRST STOP – CAPE KERAUDREN

Our last blog finished with us at the DeGrey River campsite, north of Port Hedland. We had a week to burn before we were to return to Port Hedland for some work on the car. Where to go? I know Nirbeeja would have returned to Carawine Gorge in the blink of an eye, but it was quite a distance from Port Hedland, so we opted to travel instead up the coast. After a couple of false starts we arrived at the Cape Keraudren Coastal Recreation Reserve (try saying that after a couple of wines). Cape Keraudren is at the southerly edge of the well-known Eighty Mile Beach, so we thought it might give us a taste for the area.

We planned to stay for two nights, but stayed for five. We loved it. The area was full of wildlife, the beach was beautiful, we had our first sighting of Brolgas on this trip and we saw many magnificent kangaroos. We were camped beside Cootenbrand Creek, a lovely sheltered spot that kept us entertained with its massive tidal variations and pale aqua waters. The only drawback was that the campsite was on a limestone shelf, making it impossible to use pegs to secure the camper trailer. So we improvised, tying the ropes to large rocks and using boxes to support inside the walls of the bedroom. Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

We had read about the massive tides of northern WA, but Cape Keraudren gave us our first experience of them. At low tide, we were able to wander out across the tidal flats seemingly forever, watching the soldier crabs scuttle for the safety of their sand-holes. With child-like glee we explored the fringes of coral reefs which were only exposed at low tide. At high tide we watched the water in the creek come threateningly close to our campsite, and ventured into the mangroves, spellbound by the inexorable march of the incoming waters through the mass of mangrove roots. We also spent hours wandering the beach collecting shells; neither of us could recall seeing so many beautiful shells in one place.

The Reserve has a full time ranger. Initially we had a couple of misgivings about his slightly macho manner (there was a little bit of Russell Quoit in there somewhere) but we really warmed to him, finding inspiration in his absolute passion for wildlife and benefitting greatly from his local knowledge. Upon our arrival, he noticed the “Brolga Healing Journeys” sign on our car, and mentioned that we might be lucky to see some Brolgas in the reserve. We certainly were; on our first afternoon there we were privileged to witness a flock of Brolgas dancing. It was thrilling and beautiful and we were enthralled to see these large birds leap about a metre into the air. We had read that the dancing behaviour was contagious among Brolgas, and that appeared to be the case with the small flock we watched. One Brolga commenced the dance and in no time they were all leaping about. We also saw some Jabirus (Black Necked Storks) in the same area.

The ranger also told us that the park was home to every species of raptor (bird of prey) in Australia, and that it also had large numbers of kangaroos, including seven foot tall ‘blue-fliers’ and eight foot tall ‘red fliers’. “Yeh, sure!” we thought. He also told us about the blond and albino roos in the reserve. We thought this was all a bit of grandstanding, but we were later to eat our words. The ranger must have realised that we were a couple of wildlife enthusiasts, because he allowed us to visit an area of the park that is usually off-limits to visitors. At dusk we drove through the area at crawling pace, and in no time were surrounded by the heads of roos popping up everywhere out of the tall pale grass. There were blond roos, yellow roos, orange roos and enormous red roos. They were everywhere! We quickly decided that the ranger’s claim of eight foot giants was no exaggeration – some of the males were enormous, with massively developed chests and forearms. As we drove out from the area at last light we were met by the ghostlike vision of a huge, blond male roo watching us from identically coloured grasslands. It was quite a thrill.

We returned the following day to thank the ranger for that opportunity, and he gave us some amazing information about the roos. He had watched the roos in the reserve fishing in rock pools. He had never seen or heard of such behaviour by kangaroos; neither had we. He added that the roos had shown enormous patience, watching into the water, perfectly still, until the fish drew near, suddenly catch it with a forelimb, throw it over their shoulder, then go and eat their fish dinner. It recalled for me the fishing technique of the North American Grizzly Bear. More information: we had always thought that roos were quite stupid and that their apparent lack of any road sense was testimony to that. The ranger said that he had once shared that belief, until he learned that they have incredible eyesight, including almost infrared vision at night. When the bright lights of a car come upon them at night, they take several seconds to move from this enhanced night vision to normal, and in the small time taken for that adjustment they often met their doom. They also have opposable thumbs on their forelimbs, with greater dexterity in their thumbs than all the apes other than humans. One female roo had adopted him and spent quite a deal of her time wandering into his ranger quarters, helping herself to lots of goodies from his fridge. This is despite the fact that he had changed the “child-proof” lock on his fridge three times in an attempt to keep her out of it. As he said, being able to solve problems is a sign of intelligence, not stupidity. He was full of information about this beautiful member of our native fauna. Even if what he said was only half true, he gave us plenty of food for thought.

We found the blond roos particularly interesting. These arise from a recessive and quite rare gene, and the ranger proudly informed us that there were 14 blond roos in the reserve. They blended perfectly into the Spinifex and other native grasses in the reserve.

There was one other facet of staying at Cape Keraudren that fascinated us. We were able to get wireless internet reception most evenings for the couple of hours after dusk. Normally we are hard pressed to get reception 15km away from the transmitter, and the nearest transmitter in this case was in Port Hedland some 100km as the crow flies and 140km by road. Our reception had something to do with the atmospheric conditions and the shape of the coastline. I guess it’s the same as listening to far distant radio stations at night.

So we were able to send and receive emails and connect to the net a long way from civilization. We are constantly reminded during our travels of just how fortunate we are to live in these times. This accessability is a double edged sword of course, and there are times when it has been nice to know we have been out of contact, but I certainly love being able to connect to the internet. Nirbeeja has on many occasions joked that we could never live in a totally remote area because I would have to have my internet connection, and she always laughs that the first thing I do when we arrive in a town is check the email. Still, at Cape Keraudren you had to earn your internet connection, in my case by standing at the top of a sandhill in the dark and in the wind, being eaten alive by sand flies, holding the laptop high enough to maintain the connection. One night I lost my balance due to all those factors (and no, I wasn’t drunk), and rolled down the dune, turning a complete 360. I am glad to report that I somehow managed to keep the computer away from the sand. I am also glad that no-one noticed my less than graceful descent!

We returned to Port Hedland, had the car serviced (ie we had the war-wounds from our adventures into Rudall River National Park repaired) and headed north-east up the highway again. You beauty, Kimberley bound at last!

We stayed at two highway-side free camps on the way to Broome. At both sites we were surprised to see Red Winged Parrots, the first we had seen since leaving Louth on the Darling River of NSW almost two years ago. They were a colourful and spectacular sight as they flew, screeching to each other on the wing, from flowering tree to flowering tree. We were also interested to notice a marked change in the pattern of vegetation, with beautiful tall Grevilleas and Hakeas in full flower and other flowering trees covered in almost intoxicatingly scented blooms.

AT LAST WE ARRIVE AT BROOME – ALONG WITH EVERYONE ELSE

We arrived in Broome, nearly two years since our journey began. Broome had always been high of the list of places we wanted to visit while we were planning our trip. It held such an exotic appeal; in the far north west of the continent, on the doorstep of the Kimberley wilderness, a dreamy, relaxed place with a rich and integrated multi-cultural history so different from most other Australian towns. We also knew that a great many other Australians, and for that matter foreigners, also shared our interest, and that as a result Broome was undergoing a tourism boom that was likely to tarnish the very qualities most of us sought there.

So we arrived with open minds, hoping for the best but expecting otherwise. And Broome was a bit of both really. There remain hints of the Broome of old, with its harmonious blend of European, Malay, Japanese, Chinese and Aboriginal races and cultures, but they must now be sought out in the profusion of cafes, tour company offices and jewellery shops specialising in Broome’s famous pearls. The Chinatown area epitomizes the new Broome. The old buildings have all been restored and converted into modern shops, in many cases only the original façade gives evidence of times past. I walked down Johnny Chi Lane, and while it was quite narrow and pretty with its overhanging trees, and its very name spoke of times past, there was little now other than its name to separate it from any other shopping lane in the country. So there are hints of old Broome but the social and commercial fabrics of Broome have largely changed. There are however some great points; Broome is a very friendly place, and appears to remain true to its highly integrated multi-racial and multi-cultural origins. The locals, who are fairly easy to spot among all us tourists, are friendly and open. They greet you with a ready smile and seem happy to interact. And we were fascinated to notice that many of the locals showed racial characteristics from the whole melting pot of Broome’s past.

While the car was being serviced I seized the opportunity to walk the streets of Broome, in particular exploring ‘Old Broome’ and the area around Town Beach. Many older style buildings remain in those areas, some quite run down, but at least this area gave me a better idea of the town’s past.

Broome is certainly favoured by its surroundings. Cable Beach is beautiful, living up to all the hype. You cross a small hill to be met by a magnificent long white sandy beach, loaded with tourists. And the nearby Gantheaume Point is stunning, with multicoloured rock formations and sparkling surf. At extreme low tide dinosaur footprints are visible in the rocks, but I was there while they were covered by the ocean and I had to be content with concrete replicas.

Throughout the winter months Broome bursts at its seams with tourists. The population explodes from around 15000 during the wet season to around 60000. All accommodation is fully booked and overflow facilities are set up at places like the Pistol Club to house the visitors. All at premium prices too. I guess that’s just the law of supply and demand in action. The whole Broome region is over-run with tourists. Even the highway side free camps over 100km from Broome are full by mid afternoon – and these offer little more than a dusty parking area and drop toilet. We can only hope that some better balance is found up here before the flocks of visitors (of whom we are admittedly two more) tarnish the natural beauty of the region.

The weather was gorgeous, explaining why so many people go here. We had to remind ourselves constantly that this was winter. Warmish nights followed by days in the low to mid thirties were the norm. Quite lovely.

We were fortunate to have pre-booked a campsite at the Broome Bird Observatory, some 25kms out of town, situated on Roebuck Bay. The road in wasn’t too great – 16kms of heavily corrugated sand badly in need of a grader, but the rewards were enormous. We had a lovely bush campground, quiet and shady, and quite fittingly there was an abundance of wildlife.

The shores of Roebuck Bay near the Observatory are regarded as one of the top five spots worldwide to view migratory wading birds. Just don’t ask us what the other four are! We love our wildlife, including our birds, but we were a little in awe of the knowledge of many of the people staying there. Nirbeeja and I have a fairly limited knowledge base of wading birds – we’d be lucky to identify a few of the hundred or so species known to visit Roebuck Bay. If asked to describe one I would probably answer that it was as “a pretty little pale grey bird with a long pointed beak.” Such comments might have me banished from the ornothological priesthood of the Observatory. I jest really, because all the people there, both staff and visitors, were friendly and eager to help us identify what we had seen. I can now identify a Black Winged Stilt, a Red Knot, a Great Knot, a Black Necked Stork (Jabiri), a Bar-Tailed Godwit and a Duck Billed Tern as well as your common garden variety Silver Gull, at a thousand paces! The hotter months from October onwards offer the best viewing of the birds, apparently with many hundreds of thousands of ‘temporary visitors’ on the shores. During Australia’s winter, most return to eastern Siberia and Mongolia to breed during the northern hemisphere’s summer. As a result, we didn’t see huge bird numbers during our stay, but it is all relative and there still seemed plenty of birds about, and we were happy with what we did see. We learned that juvenile birds, last season’s offspring, stay in the region over our winter building their strength and weight, while the adult birds return to the northern hemisphere to breed. Of course, winter in the Broome region is hardly tough going, as we discovered.

The surroundings of the observatory were unforgettable. The sands of Roebuck Bay feature an amazing variety of colours, from deep rich red from the Pindan cliffs, to white sands, to black volcanic-looking rocks. The water varied from crimson-red near the shore to aqua further out. The bright green Mangroves completed the rainbow like vista.

The bush surrounding the Observatory was home to many Agile Wallabies. These timid little wallabies are certainly well named. At the first sight of one of us they would bound off at a startling pace into the scrub, slapping the ground in warning as they went. This made the job of photographing these beautiful little creatures quite a challenge! At night though, they became more adventurous, and we were often woken by the sound of them moving about and eating from the leaf litter directly outside our camper.

Once again we were reminded of the remoteness of this region, which is easy to forget when you are immersed in the tourist hustle of Broome. We decided to upgrade the suspension on our car to give it a lift when towing, to improve its performance in very rough 4WD country, and possibly most important of all, to make travel over WA’s endless outback corrugations more bearable. We also wanted a couple of new tyres. We weren’t going to tackle the Gibb River Road without being well prepared. All this is possible in Broome, provided you wait for the parts to arrive. So once again, we had a week and a half to spend before we could get the work done. We recently heard that WA stands for Wait Awhile – now we know why!! (The Northern Territory is by all accounts similar, with people joking that NT stands for Not Today, Not Tomorrow, especially whenever you need anything done. We amused ourselves during the long hours on the road dreaming up similar sayings for the other states, but will spare you those for now.)

DERBY – TOWN OF THE BOAB

From Broome we headed north to Derby, some 220 km further up the road. We are happy to report that the tourism boom is yet to overwhelm Derby. Sure, the large caravan park was full to bursting, but the town itself had a sleepy, friendly charm. Any town with Boab trees lining its streets can’t be too bad!

Derby doesn’t boast the pretty coastline of Broome, and that probably goes a long way to explaining why it is yet to experience its own tourism boom. There is however still plenty to explore in the region, and Derby has its own rich history.

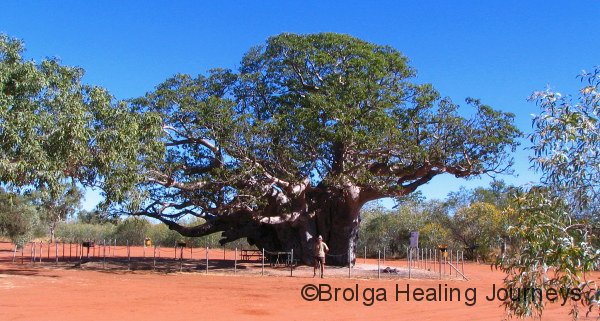

Derby is infamous for its Prison Boab Tree, where Aboriginal prisoners were once held overnight, chained both inside and outside of the tree, before they were transported the following morning to Derby gaol. Often these ‘prisoners’ had done little more than kill cattle for food on land that had belonged to their people for thousands of years, but from which they were now being dispossessed. Others were hardly prisoners at all, but were rounded up as slaves to work on stations and settlements further south. Their white gaolers/slavers were known at the time as ‘blackbirders’.

We learnt that this beautiful tree, estimated to be over 1500 years old, is regarded by Aboriginals as one of several Boabs (or larrkardiy) in the Derby region to be imbued with special mystical forces. The Aboriginals call these special trees malaji, and according to Ngarrangkani or Traditional Law, people who injure a malaji, or intrude upon one without authority, expose themselves to the prospect of retribution by these forces. Dispersed throughout the Kimberley are other larrkardiy that are believed to harbour extremely severe and potent powers. These powers may be invoked by senior ritualists to punish people who violate traditional law.

We can only hope that the white men who chose to desecrate this particular Boab by using it as a prison tree were unaware of its special spiritual significance to the Aboriginals, though given the horrendous treatment of Aboriginals by early white settlers in the region, we would hardly be surprised. But the tree still stands, old and beautiful, in leaf and flower on the day of our visit, no doubt the wiser and more powerful for having borne witness to that dark period in our history.

The Derby region marks the south-western boundary of the rugged ranges for which the Kimberley is so well known. Those ranges are world famous for their abundance of rock art sites featuring Wandjina and Gwion Gwion (or Bradshaw) figures. It was therefore fitting to find the Mowanjum Art Centre located nearby, just a few kilometres from the start of the Gibb River Road. This impressive art centre features paintings by many well-known Aboriginal artists, including Donny Woolagoodja, the elder who designed the famous Wandjina head that appeared to rise up out of the ground during the Opening Ceremony of the Sydney Olympics. The art centre features some beautiful art works, displayed by artist family group. Against all odds we managed to resist buying any art during our visit, despite their beauty and reasonable pricing; we just have nowhere to hang them in our camper trailer.

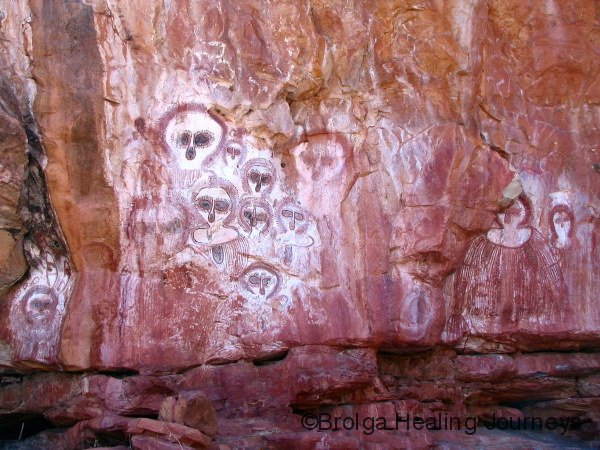

The Wandjina represents the creator spirit for the Aboriginal people of the Kimberley region. These striking figures, some dating back thousands of years, are found throughout the Kimberley in rock art sites. The Aboriginal people treat these sites with respect and caution, indeed often approaching Wandjina sites with some fear. They tend not to stay at sites for long. Initiated elders were responsible for refreshing the Wandjina figures in their tribes’ sacred sites in traditional times, in other words, repainting the figures. This still occurs in a handful of sites but many images are now fading due to the loss of traditional ways. The Aboriginal people believed that the Wandjinas were responsible for bringing the annual rains and storms to the region, and thus the people refreshed the images annually to ensure the return of the rains and renewal of fertility to the area. Wandjinas are usually portrayed with a halo-like ring around their head and no mouth; they are all seeing and knowing and have no need for speech. In my experience every Wandjina art site is special; they are indeed powerful, spiritual places that inspire respect and awe. A visit to any Wandjina site is an amazing experience.

One of the things to do in Derby is to watch the sunset from the local jetty and to watch the swirling waters off the jetty as the 12 metre tides race in or out. The sunsets weren’t too bad, but we found the crowds far more interesting. People arrive hours before sunset to secure their spot, taking deckchairs and refreshments.

On our final night in town we went to the Spinifex Hotel to see a Diesel concert. It was a great night and we were impressed by Diesel’s musicianship; a rootsy mix of blues, rock and pop. The local crowd was entertaining and Nirbeeja and I did our best to raise the average age of the audience!

FITZROY CROSSING

Heading out from Derby, we started along the Gibb River Road but it proved too rough with our pre-upgraded suspension (but like General Macarthur we vowed to return!), so we back-tracked and drove instead along the bitumen to Fitzroy Crossing. We had stopped overnight at Fitzroy in a whirlwind tour of the Kimberley with a group seven years ago, so it was nice to spend a couple of days seeing the area more thoroughly. We walked along Geikie Gorge admiring its multicoloured limestone cliffs which in Devonian times, some 450 million years ago, comprised a sea-bed. As with most things in the north-west, we were only able to appreciate the magnitude of the gorge as we drew closer. The cliff walls reach 30 metres high and the lower 16 metres are bleached white by the annual flood waters coursing down the Fitzroy River. At its peak each year the Fitzroy can reach up to 15km wide, and travels 750km to the ocean. The walk along the gorge gave Nirbeeja her first fleeting glimpse of the Crimson Finch and introduced us to some richly scented native flowers.

In Fitzroy Crossing we stayed at the Crossing Inn Caravan Park, adjoining the Crossing Inn, built in 1897 and thus the oldest ‘watering hole’ in the region. With travel now so much easier most people barely stop in Fitzroy Crossing, but in days of old they would, no doubt, have collapsed in a thankful heap at the Crossing Inn bar. The Inn and caravan park are now owned and run by local indigenous people. The caravan park was immaculate, and we thoroughly enjoyed our stay.

WE EXPLORE MIMBI CAVES – AND ARE TAKEN BACK TO THE DREAMTIME

About an hour’s drive east from Fitzroy Crossing are the Mimbi Caves, still part of the same Devonian Reef. The caves are part of the traditional lands of the Gooniyandi people, and the only way now to visit the caves is to join a day-tour run by the Girloorloo Community. We were more than happy to join such a tour because we feel these provide a valuable opportunity for Aboriginal people to retain ties to their culture and lands and for non-Aboriginals to gain a deeper insight into and respect for that culture.

Radiocarbon dates on charcoal from ancient fireplaces reveal that Aboriginal people have lived at Mimbi for at least 40000 years. Through Dreamtime stories, the custodians trace their traditional ownership of Mimbi back even further. An important Gooniyandi story for Mimbi Caves is called “The Blue-Tongued Lizard and the Mudlark”.

Long ago in the Dreamtime there lived a blue tongue lizard and a mudlark. The blue tongue lizard had six babies that she used to carry around on her back. One day a big flood was coming and the blue tongue lizard wanted to get to higher ground so she asked the mudlark if she could leave her babies high up on her nest. The mudlark said “no, I only have room for my kids”. So the blue tongue lizard and her babies got swept away with the flood and they are found today at Looma community 85km south of Derby [around 200km from Mimbi].

Apparently there is a large rock formation resembling a blue tongue lizard near Looma and the local people tell a similar Dreamtime story.

Gooniyandi people believe marrowa the blue tongue lizard in this story made the hills and the landscape surrounding Mimbi Caves. The rock art and engravings are further evidence of Aboriginal peoples’ long occupation of Mimbi. In relatively recent times, the caves were a hiding-place for Aboriginal people, especially from pastoralists and the police, up to the middle of the 1900s.

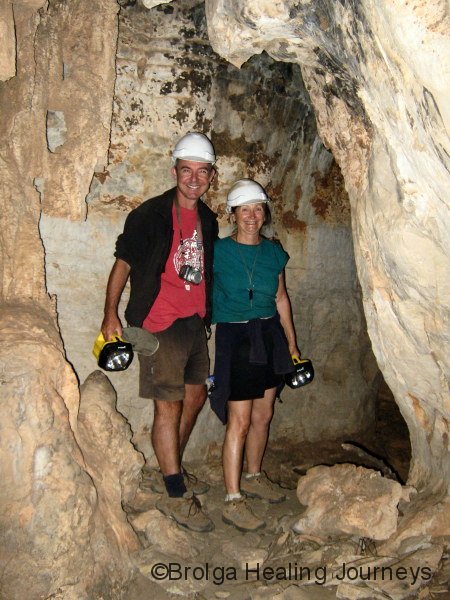

And coming right back to the present: the tour was fantastic. We were led by a young Aboriginal guide, Joe, whose grandfather had initiated these tours. When Joe’s grandfather died his family decided to continue to run the tours to honour him. Joe led us through a labyrinth of limestone caves, making us grateful that we weren’t on a self-guided tour where one wrong turn could easily get you lost, injured or both. The crystal-clear waters in the caves were home to pale cave-fish and bats clung to the walls. Rock art adorned the entrances to some of the caves. Some of the art consisted of petroglyphs (engravings), while others were painted, now with only the deep red staining remaining on the rock face.

We had a morning tea and damper made by Joe’s mother. Our final stop was at what was once the birthing cave for the local people. This cave certainly had a womb-like quality to it, and rock art lined its walls.

Mimbi Caves are reputed to be one of WA’s largest cave systems and are largely unexplored. The tour currently ventures into one small area of the cave system, but even so we were amazed at how many branching passageways greeted us on our tour. So many pathways beckoned! The caves also contain the most significant fossil fish site in the southern hemisphere. We were told that many of these fossil fish have the same pattern of bones as humans and land animals and their skeletons include humerus, ulna and radius bones.

The Girloorloo Community plans to develop a camping site to enable visitors to stay overnight, and also intends to open up further sections of the caves for tours. We were inspired to see such positive work being done in such a community and hope one-day to return, to camp on-site and visit further areas of the Mimbi Cave network. Good luck to the Girloorloo Community!

From Fitzroy Crossing we wandered our way back to Broome, camping at a couple of roadside free-camps. These camps offer the most basic of facilities; rubbish bins and drop toilets, but given the numbers of travellers in these parts they were full by mid afternoon. We stayed two nights at a site around 130km north of Broome, and met some fabulous people there, sharing a couple of bottles of wine and swapping details of great places to visit. These are friendly places but like anywhere, you find some people with whom you feel an instant rapport, and others who you’d prefer to avoid. Ahh, humanity! But our experience has mainly been great in these places and we have gladly met up again with some of the people we have met at them.

BACK TO BROOME – AND LOTS MORE BIRDS

It was with a sense of déjà vu that we drove to the Broome Bird Observatory (BBO). Once again we planned to stay for a few days, and once again I was due to drive in and out of Broome for car-stuff. Oh well, at least it was a beautiful place to stay. And it proved even better this time than our first stay.

The ‘car-stuff’ to which I alluded – getting the suspension upgraded to a full-on 4WD Old Man Emu kit for our trusty car – has been a Godsend. The corrugated sand road into the BBO, which had always threatened to shake our rig apart, now seemed benign, a slight shudder. Surely they have re-graded the road, we wondered, but no, it was the same road. A sigh of relief from us, because the upgrade wasn’t cheap, though we have since decided that it was worth every cent.

We loved our stay at the BBO so much that we kept extending, to the point where we had grown close enough to some of the resident staff for farewell hugs upon our eventual departure. We love the BBO, and hope to return for a longer stay for some volunteer work in the future.

During our stay we went on the 8 hour Lakes Tour offered by the BBO, led by Eduardo, a Columbian ornithologist. He led our small group through the back blocks of the enormous Roebuck Plains Station to three permanent water bodies – Taylors Lagoon, Lake Campion and Lake Eda. Out came the telescopes supplied by the BBO and we were enthralled by the variety and number of waterbirds, raptors circling overhead, and bush birds between sites. All up we saw 67 different species of birds that day, including around 30 new species for Nirbeeja and me. The sight of around 100 Brolgas at the final waterhole, Lake Eda, capped off a perfect day of birdwatching for us. For anyone interested (particularly Nirbeeja’s ex-wildlife colleagues in Canberra), we have listed the species we saw on the tour, at the end of this blog. We found the day really exciting and it was great to see that ornithologists Eduardo and Mary (an American working at BBO) were just as excited as us to see the birds. Actually, at one stage we were worried that Eduardo was getting a little too excited about it all, with him commenting, as only a passionate Latin American could, about the immaculate white rump of the Swamp Harrier! By all accounts some of the birds we observed that day are rarely seen in the region – such as the Varied Sittella and Golden-headed Cisticola. For us most of them were rare.

Enlivened by our day of birdwatching and now feeling part of the gang, we volunteered, with a degree of reluctance it must be admitted, to help out with a sea-grass monitoring project on Roebuck Bay. Our reluctance was due entirely to the timetable. Because of the massive tidal variations in the region, the monitoring was only possible at low tide, which was scheduled for sunrise. Unfortunately this meant getting up at 4.15am, if we were to travel the 30kms to the monitoring site in time to help out. Oh well, we looked at each other to confirm that, yes indeed, we were crazy, then put up our hands to volunteer. The prospect of hot coffee and muffins on offer helped convince us to go. Despite the sleep deprivation, it turned out to be a great experience. We didn’t find a lot of sea-grass, but we did find many other interesting sea-creatures, some of which were unknown even to our marine-biologist organiser. She informed us that knowledge of the sea-life around Roebuck Bay is far from complete. She said that the shortage of sea-grass in the area could be seasonal, but could also be due to increasing pollution and recreational boating in the region. All this made us wonder about the possible long-term damage that something like the proposed Kimberley Gas port may cause in the region. The Kimberley is very much the last frontier and largely untouched, but we as a society seem hell-bent upon pillaging the area. If only we had learnt something from the irreparable damage ‘progress’ has reaped upon the eastern states.

The tide came rushing in just as we finished our monitoring project, so we headed in to the Broome Town Beach Café for breakfast with a couple of the staff from BBO, then accompanied them to a fascinating seminar entitled Predicting and Preventing Future Disease Outbreaks. The lead speaker was Dr Peter Daszak, President and Disease Ecologist of the New York based Wildlife Trust. Given the worldwide concern about the current outbreak of Swine Flu, his talk was particularly topical. His paper discussed research into cross-species transfer of disease and modelling of future outbreaks. We were unsurprised to learn that human travel and ecological interference were the most likely vectors for the spread of disease. The sheer volume of air-traffic in the modern world has greatly magnified the potential spread of disease. Dr Daszak made the observation that spraying air-craft cabins with insecticide was virtually ineffective; far more useful was laying down surface insecticide in cargo holds of plane where disease-carrying flies and mosquitoes are more likely to reside.

After the bird-flu epidemic, when migratory birds were suspected to be possible carriers, it was reassuring to learn that wildlife is little to blame for these outbreaks. As Dr Daszak observed, if there is any hint that wildlife is to blame for disease outbreaks, many people are only too willing to solve the problem by choosing to eradicate the wildlife.

The problem in fact usually goes the other way, although there have been instances, particularly in third world countries, where close work with animals has introduced disease into the human population. But generally, humans are responsible for spreading far more disease to wildlife populations than the other way around. We learned that several species of frogs rapidly went from abundance to extinction due to human impact upon their ecosystems, introducing a herpes type disease to the frog populations against which they had no immunity. Three species of frog within one area of Queensland went from well-populated to extinction within months. One thing that Nirbeeja and I suspected, but which went unremarked in the presentation, was that environmental degradation may be weakening the immunity of wildlife populations and making them more susceptible to disease outbreaks.

We were interested to learn that Malcolm Douglas, the well-known TV presenter and wildlife park owner in Broome, was also present at the seminar (his great booming voice from two seats away nearly knocked us off our chairs). He told the gathering a heart-breaking story. His wildlife parks have been engaged in a long-term project to breed Bilbys for their re-introduction into suitable areas of Western Australia. His parks had also been involved in monitoring Bilby numbers state-wide. The breeding program had been progressing steadily over several years until only recently when within 48 hours the entire population of Bilby’s at the wildlife sanctuary died. Veterinary specialists in Perth are still trying to identify the cause, but early work suggests the disease was inadvertently introduced by a human carrier. Recent monitoring in the Great Sandy Desert had found similar dramatic and sudden declines in Bilby populations. We can only pray that some remote Bilby populations have been spared. Otherwise many years of dedicated work, by a great many people, may have been in vain. Is there any solution to this problem? Human travel and human progress are major contributors to similar disease outbreaks in wildlife worldwide, yet there seems little likelihood of humanity changing its approach. Nirbeeja and I are enjoying our travels, as are many other people, but we may well all be part of the problem, despite our love of wildlife. We are often unaware that our shoes and car tyres may carry bacteria and fungi into new areas.

The research by Dr Daszak and his team suggest the worst areas for introducing disease into wildlife problems are third world countries, especially those undergoing economic booms. With China, India and many countries in South America on the path to rapid expansion, the future for wildlife in many areas could at best be described as uncertain.

AN EVENING WITH TONCHI

With this sobering information in our minds, we had some pleasant relief that evening when we went to the Divers Tavern in Broome to see a gig by Tonchi McIntosh. Tonchi, you may recall, is a musician originally from Bourke, outback NSW and now of Melbourne, who writes poignant songs about the Australian bush and its people in an awe-inspiring range of musical styles. (We have written glowingly about Tonchi in earlier blogs.) Tonchi lived up to all expectations, and surprised us with the wealth of new material he played. He has been busy indeed since we last saw him, at the Fairbridge Festival, south of Perth, on ANZAC Day 2008. Present with us in the audience were Russell and Pam from the Queensland Sunshine Coast, whom we had met at one of the free-camps north of Broome. We are certain that Tonchi can now count them among his fan-base. After a tiny bit of memory jogging, Tonchi remembered us and very kindly gave us a double CD of a musical collaboration he completed with Andrew Hull and Mick Daley to retell the stories of the people and history of White Cliffs, NSW. Good on you Tonchi!! We are eager to see whether he recognizes us, unprompted, the next time we see him.

GIBB RIVER ROAD – HERE WE COME

OR

“TOUGHEN UP, THIS IS THE KIMBERLEY” (advice we overheard from a real Kimberley character to a couple of other travellers)

Finally, our car ready for the Kimberley, and packed to the gunnels with supplies for the wilderness, we headed out of Broome, bound at last for the Gibb River Road.

This time travel along the road much easier. It was three cheers for our Old Man Emu suspension from Nirbeeja and me.

First stop was Windjana Gorge, in the ancient Napier Range. The gorge itself cuts 3.5km right through the Napier Range – a limestone range formed at same time as Mimbi Caves and Geike Gorge. On our last tour to the Kimberley 7 years ago we had walked in and straight out, getting barely a glimpse of the gorge. This time could explore properly and enjoy the area’s riches. The gorge was full of beautiful limestone formations, sunsets glowing off the cliff-face, along the length of the gorge fresh-water crocodiles sunbaked on the sands, archer fish shot down their prey with a spit of water, and there were lots of birds. Nirbeeja even spotted the elusive Small Eared Rock Wallaby.

Part way into the gorge is a huge limestone rock, named Bandangnan, straddling the water. To the local people this was the boss-man rock – the rock in charge of Windjana Gorge. At the other end you come to an area named Djamburrwurru, that translates as ‘roaring of the waters’. When the flood waters pass down the Lennard River each wet season, they apparently cause an enormous roaring sound.

And some way around the escarpment beyond the end of the gorge I located Wandjina art site, named Langurrngurru after the chief Wandjina portrayed at the site. This was a spectacular place, situated next to a deep cave, high up on the cliff-face with breathtaking views of the surrounding landscape, grasslands and Lennard River. A magnificent stand of boab trees are aligned like guardians along the base of the cliff. There is extensive art at the site, though much has faded through natural decay. Fortunately, this is not an easy site to find and relatively few people visit it. There was no evidence of graffiti or deliberate damage to the site.

Climbing the cliff to the site I was at first disappointed to hear other voices – but met Graham and Merrilyn, a couple from Melbourne who had been to the site 15 years ago. Graham said that revisiting this special place was on his hundred things to do before he died. We shared a sense of awe at the site and found we had many attitudes in common. We were all glad that it was relatively inaccessible, because this meant there would most likely be less damage to the site.

Before going to the site I had first checked with the Aboriginal ranger at the campsite that it was okay. I had also asked if there were other sites in the area I could visit. He answered that there were other sites near Windjana Gorge but non-aboriginals couldn’t visit. I was fine about that, respected it and in fact I am glad that some sites are restricted like that. I think when he realized I had no problems with being told ‘no”, he proceeded to give me details of sites near Tunnel Creek that I could visit. I knew about one of them but not the other. So I regard that as a real bonus.

Nirbeeja and I spent a big night with our new friends Graham and Merrilyn at their campsite; indeed far, far too many wines were consumed. We spent an extra day camping at Windjana Gorge while I recovered from a massive hangover! We had so much in common it was like meeting up with old friends. We will stay in touch (and if you read this Graham and Merrilyn we fully intend to take you up on your offer for us to visit your holiday house on Bruny island in Tassie!!).

The other ‘must see’ attraction in this part of the Kimberley is Tunnel Creek. As its name suggests this creek has tunneled its way through the Napier Range and can be walked its entire length, taking you from one side of the range to the other. The tunnel is 800 metres long, with an ancient cave-in around halfway providing some light. Otherwise, the pitch black tunnel must be traversed by means of torch-light, and takes you through a series a cold pools from one side of the range to the other.

At the far end we found an interesting rock art site and spent some time exploring along the creek, and around the rock-faces

We had a ‘very interesting’ return trip through the tunnel. The batteries to our torches proved not to be as fully charged as we thought, with the result that we could barely see our way. This wasn’t too bad, until I found myself up to my chest in cold water, with both cameras underwater. You can imagine the language and the self-reproach that followed. To cut a long story short, I am very pleased and relieved to report that both cameras are working fine now, albeit after some time spent drying out. Who said there are no such things as miracles.

Nirbeeja advised me later on (once the cameras started to heal) that she had silently begged and begged the Universe to ‘please make the cameras work again’, as the thought of the dramas of me without a working camera was just too much to bear for her.

On the instructions of the ranger, before entering Tunnel Creek we had climbed up to view art-work high up the cliff near the entrance. We simply couldn’t believe someone could put it there. There appeared hardly anyway up, let alone doing it in bare feet and with little light.

Tunnel Creek is also famous because it provided a hide-out for the Aboriginal outlaw Jandamarra, who was on the run after shooting a white policeman, Constable Richardson, nearby in 1894. Jandamarra became a legendary figure among his people, displaying near superhuman feats in eluding the police for many years in this region. Moreover, the local Aboriginal people put up a fierce resistance to white settlement in the region and to cattle being introduced into their traditional lands. Quite rightly, this cattle was on their land so they felt free to kill it for food. The policemen, displaying the attitudes of their times, eventually weakened Jandanmarra’s resolve by systematically killing off innocent members of his tribe. Following the death of over one hundred of his people in this way, Jandamarra grew disheartened, and was killed by an Aboriginal tracker near the entrance to Tunnel Creek. Interestingly, at the nearby ruins of Lillimilura Police Station, there is a plaque commemorating the death of Constable Richardson, but there is no such plaque commemorating the innocent Aboriginals killed in retribution by the early white settlers.

We departed the Windjana Gorge camping area to continue our way along the Gibb River Road. The road took us across the King Leopold Ranges, named after some Prussian ruler who had probably never heard about Australia, let alone the Kimberley, but such was the want of our early settlers and explorers. The King Leopold Ranges are rugged and spectacular. And ancient. The rock here is estimated to be 1600 to 1800 million years old.

This section of the road was particularly rough, with deep hard corrugations and rocks the size of house bricks scattered along its length. This was tyre destroying country for the unsuspecting! Given the nature of the surrounding countryside it was some feat building a road of any description through it.

We left the Gibb Rough Road and headed in to the Silent Grove campsite en route to Bell Gorge. This side track was again quite rough, but careful driving saw us through intact (many people we had spoken to had suffered a couple of punctures on this stretch, probably because of excessive speed).

Silent Grove was a lovely spot, nestled beside a sparkling, bubbling creek and full of birdlife. Here we had our first glimpse of the Crimson Finch, a beautiful little bird. We were camped beneath a majestic boab and simply loved our stay there. We travelled up to Bell Gorge, a stunning place. The river dropped over a fair sized waterfall, and then went down through a seemingly endless series of gorges, to other waterfalls, and off into the distance. We explored some way downstream below the track, eventually deciding that we’d seen enough. But it was a difficult decision to stop our explorations, because each new stretch of the gorge was uniquely beautiful. We could have gone on forever. The pools were clear and deep, and full of fish. The cliffs were high, ancient, and deeply coloured, and the sun was baking hot. Ah, perfect really.

Our pilgrimage up the Gibb River Road continued. We stopped at Imintji for stores and were surprised at how well stocked it was. They also served freshly brewed coffee, quite welcome after weeks on instant.

MORNINGTON WILDLIFE CONSERVANCY

We continued our journey along the next 25km to the turnoff towards Mornington Wildlife Conservancy and associated campgrounds. We had heard many great stories about the place, but hadn’t built up our hopes of getting in. Mornington limits the number of visitors at any one time, and as a result many people are unable to get in. One person we met at BBO tried three successive mornings before he got a spot. There is a 90km drive in to Mornington from the GRR and, sensibly, there is a radio booth near the GRR turnoff to contact the office and check on vacancies.

Nirbeeja had been our lucky charm on our adventure, always succeeding in getting us a spot in places that should otherwise have been full, so I suggested she make the radio call to the office. Fingers and toes were crossed. Breath held. Could she do it again? ……….Of course she could!! Had anyone happened upon us at the time they would surely have thought we were mad. We were both literally jumping for joy at the news we had a camp-spot. So on we headed, prepared for another 90km of Kimberley road (ie rocky corrugations). Well, it definitely was our lucky day, because the road had just been graded (indeed we met the grader at the far end of the track). We had a smooth drive in through some gorgeous Kimberley ranges, all shades of gold, mauve and pink, past high cliffs and escarpments, the road lined with pale gold grass as high as your chest, we forded creeks alive with birds and with heavily vegetated pools either side of the road.

You are probably sick and tired of us saying how much we’ve loved places throughout our adventures. But Mornington was something special. I would rate our stay there as one of the great experiences of our whole trip. Mornington camp is a beautiful spot, nestled among towering eucalypts beside Annie Creek, a riparian creek lined with palms, native fig trees and grasses, full of fish, fresh water crocodiles and turtles, and home to wallabies and roos. But the resident birdlife is even more special, for here are found many endangered rare and species such as the Gouldian Finch and the Purple Crowned Fairy Wren (and yes, we saw both while we were there). Families of Red Backed Fairy Wren were scattered through the camping ground, and the male in his full breeding colours is simply stunning to behold.

The Mornington Wildlife Sanctuary covers over 795,000 acres of the central Kimberley, and is owned and operated by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC). The AWC is an independent, non-profit organization dedicated to the conservation of Australia’s wildlife, funded by donations by individuals and other parties. It was established by Martin Copley, a Perth businessman in 1991 when he realized that more needed to be done to protect our endangered wildlife. Since then the AWC has grown, becoming a public charitable organization in 2001, and now owns some 20 properties around Australia covering some 2.5 million hectares (6.2 million acres). All proceeds from the Mornington Wilderness Camp are invested in conservation.

The AWC manages many research projects concerning wildlife conservation, often in conjunction with Australia’s universities.

All we can say is that everything about the operation at Mornington gave a strong impression of dedication and integrity. The sanctuary appears in great health, and wildlife is abundant. Much of their research in the Kimberley concerns the effects of fire on eco-systems.

Research into the plight of the Gouldian Finch provides an excellent example of the work AWC is doing at Mornington and beyond. Northern Australia once featured enormous flocks of these vibrantly coloured little birds, with reports of flocks in the thousands. But numbers have declined dramatically in recent decades. The Gouldian has disappeared altogether from large areas and when it is seen, it is now in small groups only; a flock of ten would be cause for celebration. The Kimberley remains the only part of the country where reasonable numbers are seen, but even there they are in worrying decline. It is estimated that Australia-wide there are only 2500 breeding pairs in the wild. Illegal trapping is partly to blame, with birds sold off as cage-pets. But the AWC has found that habitat destruction, and the restrictive behaviours of the Gouldian Finch itself, have conspired to endanger the species. The Gouldian Finch mainly eats grass seeds. Early in the dry season this consists of seeds from the tall sorghum grasses of northern Australia, but for a 6 week period at the end of the dry season, only the seed of the Spinifex grass is available and this comprises the food source of the Gouldian Finch. The Spinifex grass only sets seed in its third year. Research by the AWC found that most of northern Australia was being heavily burnt at least every second year. As a result, the spinifex grass was not reaching its third year in which it goes to seed, and thus the Gouldian Finch faced a six week period each season with little or no food. As a result, the finches would either die of starvation, choose not to breed, or breed and die of exhaustion trying to find food far from its nest. And to compound the problem, unlike other finches which choose a variety of nesting sites, the Gouldian Finch only nests in hollows in Snappy Gum trees, and these nests must be protected from other species seeking to secure the same nesting sites. So a common scenario is that a pair of Gouldian Finches finds a suitable nesting tree, fights to retain the nesting site, a fire passes through the area preventing the Spinifex from reaching a seed-bearing maturity, and the Gouldians fail to reproduce, at best trying again the following season, or at worst, dying in the attempt to find food.

But don’t despair, there is some light at the end of the tunnel! The AWC has found that a carefully managed burning program, in which some areas are burnt at the beginning of the dry season (ie very cool, controlled burns), and in which different regions are burnt in successive years, greatly reduces the incidence of destructive, widespread, uncontrolled late dry-season fires that wipe out so much of the Spinifex grass and with it the hope that the Gouldian Finch will reproduce. In recent years the AWC has managed the controlled cool burns across a huge area in the Kimberley, with the cooperation of many surrounding stations. The burn program is conducted by dropping a series of ping-pong balls filled with an incendiary mixture from a helicopter, across a carefully chosen path. They have found this program has protected the landscape from the effects of devastating fires and even better – the numbers of Gouldian Finch have improved in the region. Research by AWC into the haemoglobin levels of Gouldian Finches in the region show that these birds are also much healthier late in the dry season than they were several years ago, implying that food supplies are better. This greatly improves their chances of surviving and breeding.

This is one of many research programs being conducted by AWC into the Gouldian Finch, and other endangered species across Australia. We were blown away by the great work being done by the AWC and hope to support them with some volunteer work in the future.

Another area of research concerns feral animals and how best to manage them. Feral cats are a huge problem throughout Australia. As we all know, cats are tremendously effective predators, causing enormous damage to bird and marsupial populations. Because feral cats eat only fresh prey, they are very difficult to bait, because baits work best against creatures which scavenge for food, such as foxes. NSW Parks and Wildlife Service employs the very best trapper of feral cats in Australia, and his success rate is only 4%, such is the elusiveness of this animal. But Mornington has found that a healthy and sustainable population of dingoes in a region tends to drive out feral cats. It is a case of the larger predator driving out the smaller. And because dingoes scavenge as well as eat fresh kill, they have a much reduced effect on the populations of birds and marsupials. As a result, Mornington is ensuring adequate dingo population on the sanctuary as one means of easing the feral cat problem.

Mornington also showcases some dramatic Kimberley scenery, featuring the Sir John and Dimond Gorges along the mighty Fitzroy River. We explored both gorges, the latter by way of canoe, the only way to access it. The 60 metre high cliffs of Dimond Gorge towered above us to each side, with the only sound the light splashing of our paddles (and occasional disagreement between your two correspondents as to the best way to steer to canoe!). We returned from the 2km trip up and down the gorge weary but completely satisfied from our adventure, and can proudly report that we avoided capsizing the canoe.

We dined that evening at the sanctuary’s restaurant, refreshed by a very nice bottle of Bird in the Hand bubbly, eating beautifully cooked barramundi and vegetables and finishing off with a sticky date pudding. All this beneath sitting at a candle-lit table beneath the Milky Way, with a full moon shining through the gum trees and a campfire providing ambience a few metres away. A perfect end to a perfect day.

We went on a bird watching tour at Mornington and had a lovely time, although that morning we failed to glimpse the Gouldian Finch, the Holy Grail of Australian bird-watchers. But we are happy to report that we returned to the same pool at dawn and dusk the following day and did see

a couple of grainy photos to prove it!).

GORGES GALORE

We left Mornington, sad to be departing but in desperate need of some supplies. So off we headed, back to the Gibb River Road and then onwards towards Mt Barnett across some horrible stretches or track. Along the way we visited Galvans Gorge, a beautiful small, horse-shoe shaped gorge with rock art, relatively close to the road. We had visited this gorge 7 years ago, but if anything it seemed even prettier this time. For a short while we had the gorge all to ourselves, I had a swim while Nirbeeja did some bird-watching, then out we headed to Mt Barnett Roadhouse. We re-stocked as best we could at the small store, at great expense due to its remoteness, then ventured out to the nearby Manning gorge camp-ground.

At first, this was a let-down after Mornington, with generators humming and so many people around. Dust everywhere, tour buses arriving and disgorging hoards of travelers. Get us out of here! But we calmed down and tried to ignore the masses of humanity, focusing on the region itself. Manning Gorge is a reasonable walk from the campsite and the first part of the walk involves swimming across the nearby river to the walking track. Your pack is placed in a Styrofoam box that you push across in front of you as you swim your way to the far bank. The caretaker provided some great advice, saying that you should push the box and not hold onto it. The natural urge after all is to hold something for support when you loose balance as you plunge off rocks into deep water, and pushing the box ahead prevents you from dragging the box under with you and sending your pack and camera to the bottom of the river!

The walk to the gorge crossed a rocky plateau in hot conditions, but we were greeted at the far end by a gorgeous series of waterholes, a waterfall and high cliffs. Another prefect spot. We found life-sized Bradshaw/ Gwion Gwion paintings, then Nirbeeja and I ventured a little further than most upstream and found the perfect swimming hole, with deep water (probably 10 metres but who can say), and not another soul around, wildlife excepted. People keep asking us what our favourite gorge is in the Kimberley, and this is impossible to answer because they are all unique and beautiful, but for me this one would go close. Especially that waterhole; our waterhole. That place was serenely beautiful, pristine and to top it off we had it all to ourselves.

How could we top that? Could we? Well, first of all we had to get back on the Gibb River Road and contend with the next stretch, which proved not too bad, all things considered. We ventured in to the Barnett River Gorge, one more gorge of beauty, this one featuring hundreds of flying foxes chattering and flying around the huge paperbark trees overlooking another spectacular swimming hole.

We continued in to Mt Elizabeth Station, a family owned cattle station in the heart of the Kimberley, with a rich history. The 30km road in varied from good to atrocious, but the campsite was an oasis, as was the homestead. Squaking Rainbow Lorikeets (the Red-Collared race seen in the Kimberley region) entertained us here, as did the Station’s peacocks, which are beautiful creatures but not so endearing when they constantly jump onto your car’s bonnet to admire their reflection in the windscreen.

We travelled from the homestead out a 10km track to the Wunnumurru Gorge, the Aboriginal name for a stretch of the Barnett River Gorge that passes through the station. This was definitely a 4WD only track, the most challenging we had passed along on the whole trip. Lots of low-range rock hopping, ‘walking’ across boulders and sharp rocks. I’m happy to report that car and driver survived the experience. At the far end (10km can seem a long way after such a drive!) we reached another gorge that would vie for the title of most beautiful we have seen. A waterfall drops into a clear, deep pool which is reached across a gradually sloping sandy base from a shaded beach. Figs trees and ferns surround the pool. 500 metres downstream we saw a magnificent art-site; a special place with Wandjina upon Wandjina. A place to stand in awe and immerse yourself in the ancient spirit of the land.

After a swim we ventured across the face of the waterfall to explore the far cliff-face and were rewarded to find more rock art, less obvious than the Wandjina site but still inspiring. Prominent was an ancient drawing, several metres long, of a snake. We were admiring this painting when I looked into a couple of cracks in the rock face immediately above and below the painting, and was shocked to realize that live snakes resided there. They were quite dramatic – striped orange-brown and white. We have since learned that these were the Northern Brown Tree Snake, regarded as venomous but not dangerous. I guess their bite would make you sick but probably not kill you. We admired them from a respectful distance, wondering if the snake painting was put there to warn people, who knows how long ago, that “snakes are here”, or were the snakes somehow attracted by the site. Food for thought.

Our odyssey along the Gibb continued. We had lunch at the Gibb River itself, then headed east along the road in the direction of Wyndham and Kununurra, now with more than half of the journey under our collective belts. We had decided against journeying up to Mitchell Plateau this time around. We had been told that the falls were almost dry, we had been there before, and the final straw was learning that the road in to the falls was so bad there were now 20 cars, all casualties of that section of the track, waiting at the nearby Drysdale River Station to be towed to Derby.

Travelling the Gibb River Road itself remains a true adventure. No doubt the road has been tamed over the years. The road is graded three times each year, which may sound frequent but because there is now so much traffic along the road it deteriorates quickly and badly between grades. Indeed some sections were truly horrendous. The grader has become almost a mythical beast – news of its whereabouts travels quickly, rumours spread that the grader is somewhere along the road. People grow expectant, hopeful again. Perhaps there is a higher power. And nothing brings a smile more quickly to the face of a traveller than confirmation that graded road indeed lies ahead! And there are even small sections of bitumen nowadays, so very welcome, usually in very steep sections of the track (often know as jump-ups) and lasting about 1km. When we came across these stretches, which would finish all too soon, we were tempted to do a U-turn at each end and just keep driving up and down the smooth road till we felt ready to hit the dirt again.

Despite the graded sections, and those rare stretches of bitumen, there remain more than enough reminders that the Gibb River Road is still part of the last frontier. As one guy said – most of it is either rough or bloody rough. And the bloody rough sections make you curse it and wish you were anywhere else. You feel every bump and every kilometer travelled is hard-earned. You feel the car and trailer being shaken apart, tyres torn slowly to shreds. We did all we could to ease the burden on the car, but you always have in mind that the road can still jump up to bite you. We saw many people doing stupid things, driving at breakneck crazy speeds. The worst of the corrugations are always on the bends but many people still hurtle around the corners at 80km per hour. No wonder most of the stations display photos of 4WD wrecks, with reminders to slow down. The worst offenders are the drivers of hire cars (when we would see a Britz, Kia or Maui hire car hurtling towards us we’d shudder and head for cover). They don’t own the cars so they flog the very life out of them. Many of these drivers have no experience on rough roads and drive as though they are on the highway. And at the speeds they drive they go through tyres like there is no tomorrow. We heard of one driver having ten punctures along the Gibb River Road.

But the harshness of the drive along the Gibb makes the beauty of the countryside all that much sweeter. Once you stop, relax and take in the surroundings you are overwhelmed. This is an ancient place, uncompromising, beautiful and raw. It is one of the last true wilderness areas in the world. Every river, gorge, pool and range is unique. And you come across one after another as you traverse the region. There is a special quality to the region, a timeless presence. The Wandjina spirit still resides here. There is so much wildlife, there are so many trees covered in blossom. There are also mosquitos, sandflies and ticks; and there is the omni-present bulldust. There are travellers everywhere but such is the size of the Kimberley that one never feels crowded. Often we would have an indescribably gorgeous waterhole along a remote gorge completely to ourselves. For all we knew or cared we were the only people left in the world. At such times the roughness of the road was forgiven, indeed completely forgotten. Time stopped, words ceased and we just sat and took in the essence of the Kimberley. An agile wallaby would happen by, or a flock of the delightful little double-barred finches would make busy in the nearby bushes then hurry off to their next important stop. We would realize that a Merten’s Water Monitor had been sunning itself all along on the rock only metres from us, completely still like the rock itself. We’d watch a spiral of fish, hunting smaller prey, descend into the depths of the pool before us, disappearing into the clear waters many, many metres down. Then they would re-surface to repeat the process. A red and blue dragonfly would land briefly on your shoulder, a King Brown Snake would slither into the cracks between the boulders as you walked by, or the breeze would bring to you the rich sweet scent of the bright yellow flower of the kapok tree. Sometimes we would meet another couple and would feel an instant rapport. You simply knew that their experience was so much like ours. Later at the campsite you would talk, as if to old friends, exchange addresses and promise to make contact again. Perhaps we would, maybe we wouldn’t. To have met them there was meeting enough.

No doubt one day the road will become totally sealed. It will make the trip far more pleasant, and there were many times on the trip that we would have given anything for that. We wonder though what damage the enormous increase in visitor numbers will have on the area. You now rarely see rubbish anywhere along the road or in the gorges. Would that remain the case, we wonder?

One of the many attractions of travelling in the Kimberley is to escape civilization (come to think of it, we’ve been doing our best to do that now for 2 years). It was, however, very welcome indeed to find little hints of it as we neared the end of our adventure along the road.

Our next campsite after Mt Elizabeth was Ellenbrae Station where we indulged in freshly baked scones with jam and cream. Now, that may not sound so terribly decadent, but believe me it wasn’t bad at all after a ration of one apple for day and vegemite sandwiches. We loved the 5km drive into the station from the Gibb River Road. Every kilometer we were greeted by a sign, such as “Keep going, not long now” then “The Scones are warm, 3km to go” and finally “1km left, you can almost see us”. We loved the idea and forgave the rough track in, arriving all smiles to be greeted by the warm hospitality of the folk at Ellenbrae.

Next came Home Valley Station, with a further step up in comfort. We relaxed in a large open air bar/restaurant aptly named the Dusty Bar and Grill, and had green grass in the camping area instead of bulldust. Heaven indeed!! And they served barramundi burgers to die for. After some initial culture-shock, we realized that Home Valley offered these comforts in a low-key, relaxed way. It wasn’t too touristy or in your face. It was a great place to relax and unwind, to let a few of the corrugations settle in one’s system. The station, like so much of the Kimberley, is dotted with magnificent Boabs. At night they are subtlely lit up in the grounds to great effect, standing eerily and ghostlike against the starlit sky.

EL QUESTRO & THE END OF THE GIBB RIVER ROAD

From Home Valley we crossed the Pentecost River, no longer a challenge this late in the dry season, and ventured in to El Questro Station. We have a love-hate attitude towards El Questro. We loved the scenery. This station is blessed to “own” some of the most magnificent country you will ever, ever see. And at least they have opened it up for people to visit. The downside is that the El Questro experience certainly feels very commercial, very touristy. You know they are after your dollars! We set aside our cynicism and did our best to enjoy the country. And what country it is. The Cockburn Range towers in the distance, dramatic and imposing, equally ancient. The gorges here are gorgeous, different to the others we saw through the Kimberley. These are closer, more tropical, more intimate. Paradise, Garden of Eden, Shangri-La all came to mind as we explored. What countryside! El Questro Gorge would be the prettiest we have seen (though we couldn’t say the most beautiful, if that makes any sense). The small, secluded waterfall at the end of quite a challenging walk, climb and rock-hop up the gorge has a feeling of sanctity; it filled us with spiritual awe. The water was warm, soft and silky, refreshing and cleansing. You knew you were in a sacred space.

Zebedee Springs was similarly breath-taking. A thermal springs fills a series of clear natural pools, shaded by Pandanas palms and Livistonia palms. No one could conceive of a spa so beautiful; the perfect place for muscles and joints to recover from our strenuous climb up El Questro gorge the day before.

The following day I went on a walk up to Champagne Springs (how could I resist a name like that!), featuring different country again. After a walk along a gorge with massive, towering cliffs, I came at last to another series of thermal springs, these in the open sunlight and thus full of vivid green algae. Delicate little water plants, sundews and the like, abounded. I decided against hopping into these pools, but continued up the gorge to Gem Pool, below its own waterfall. This pool was aptly named, it was a delightful gem. A perfect place for a refreshing dip after a hot walk. I had the 10km round trip up to the springs and pool entirely to myself. What an experience!! (While I was being the adventurer Nirbeeja opted to re-immerse herself in the idyllic surrounds of Zebedee Springs, and who could argue with that).

El Questro allows visitors to take themselves to places within the property, as we did, or opt for their tours. They get bus-load after bus-load of tourists in, many who prefer to come in by bus from Kununurra rather than subject their cars to the Gibb River Road experience. Many of these tourists are elderly, which probably explains why I had the relatively arduous walk to Champagne Springs all to myself. And we both remarked that El Questro probably over-stated the difficulty of the various walks we went on, now doubt with their target clientele in mind.

El Questro probably gave us an insight into the future of Kimberley

tourism, when many more visitors will require a slightly less raw experience, and be willing to pay big dollars for it. At least El Questro appears to be making every effort to protect their environment, though we fear that the sheer number of people passing through there must have some impact.

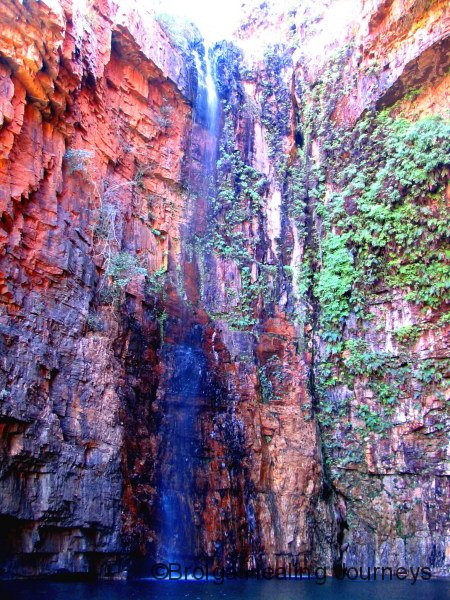

We explored a few more regions of El Questro as we neared the end of the Gibb River Road. Firstly, we visited the beautiful Emma Gorge (“Shangri-La” sprang from Nirbeeja’s lips), climbing the gorge valley surrounded by steep cliffs, and navigating around huge boulders washed down the valley in wet seasons across the millennia. At the top we were greeted by a magnificent waterfall dropping into a huge pool. We swam in the refreshing waters that weren’t nearly as icy as we’d been warned. A thermal spring came out of one wall of the surrounding cliffs, providing swimmers with a warmer section of the pool if they so wished. We were fascinated to find two streams converging downstream from the large pool; one was quite warm and the other cool.

From Emma Gorge we stopped at Gninglig, a large rocky outcrop close to the Gibb River Road, which once provided shelter and food for the local tribes. The rock featured several art sites and we became lost in imagining times past, when the Aboriginal peoples of the area lived there, hunting and simply being, with not a thought to the changes that would later come to their land. This area was once included in El Questro tours but has now been excised from them due to native title claims. We consider ourselves privileged to have been allowed to visit this site.

From there, it was a short drive to the end of the Gibb River Road. We breathed a sigh of relief, we had done it, with our car, our camper trailer and ourselves all in one piece. We felt satisfaction at having completed such an amazing adventure through the heart of the Kimberley, but also sadness at having left it for now, returning to the more civilized realms of Wyndham and Kununurra. But this was not the end of our adventures, just of this chapter.

Peter Hammond & Nirbeeja Saraswati

late August 2009

Attachment:

Birds observed during our Lakes Tour with Broome Bird Observatory:

Australian Wood Duck *

Pink-eared Duck *

Green Pygmy Goose *

Grey Teal

Pacific Black Duck

Hardhead *

Australasian Grebe

Crested Pigeon

Diamond Dove

Peaceful Dove

Bar-Shouldered Dove

Australian Pelican

White-necked Heron

White-faced Heron

Glossy Ibis

Australian White Ibis

Straw-necked Ibis

Royal Spoonbill *

Yellow-billed Spoonbill *

Black-Shouldered Kite

Black-breasted Buzzard *

White-bellied Sea Eagle

Whistling Kite

Black Kite

Spotted Harrier *

Swamp Harrier *

Nankeen Kestrel

Brown Falcon

Australian Hobby

Brolga (100 plus. Yay!!)

Eurasian Coot *

Black-Winged Stilt

Black-Fronted Dotterel

Masked Lapwing

Australian Pratincole *

Whiskered Tern *

Little Corella

Red-Winged Parrot

Red-backed Kingfisher *

Rainbow Bee-Eater

Great Bowerbird

Variegated Fairy Wren

Straited Pardalote *

Singing Honeyeater

Rufous-throated Honeyeater *

Brown Honeyeater

Little Friarbird

Grey-crowned Babbler

Black-faced Cuckoo Shrike

White-winged Triller *

Rufous Whistler

White-breasted Woodswallow

Black-faced Woodswallow

Pied Butcherbird

Willie Wagtail

Torresian Crow

Magpie-lark (Peewee)

Horsfield’s Bushlark *

Golden-Headed Cisticola *

Rufous Songlark *

Tree Martin

Zebra Finch

Double-Barred Finch

Long-tailed Finch

Australasian Pipit *

Yellow-tinted Honeyeater *

Varied Sittella *

(* denotes species previously not identified by us)

Additional species observed during our stay at Mornington Wildlife Conservancy:

Little Black Cormorant

Pied Cormorant

Intermediate Egret

Black Necked Stork

Grey Falcon

Australian Bustard

Crested Pigeon

Spinifex Pigeon

White Quilled Pigeon

Red Tailed Black Cockatoo

Sulphur-Crested Cockatoo

Red-Collared Lorikeet

Varied Lorikeet

Budgerigar

Southern Boobook (call only)

Barking Owl (call only)

Fork-Tailed Swift

Azure Kingfisher

Blue-winged Kookaburra

Purple-Crowned Fairy Wren

Red-Backed Fairy Wren

Weebill

White-Gaped Honeyeater

White-Throated Honeyeater

Banded Honeyeater

Bar-breasted Honeyeater

Buff-sided Robin

Paperbark Flycatcher

Northern Fantail

White-bellied Cockoo Shrike

Australian Magpie

Crimson Finch

Pictorella Mannikin

Gouldian Finch (break out the champagne)

Mistletoebird

Fairy Martin

Dear Nirbeeja and Peter,

I have just finished reading the blog describing your journeys on the WA NW coast and Kimberley and say “Thank you” for writing such an informative and insightful description of your travels. It was wonderful to read about the species of birds and other wildlife you saw during your travels. So many people appreciate the scenery but don’t notice the creatures that surround us.

I came across your blog when I “Googled” camping details for Cape Keraudren. We had intended to spend a night there before venturing inland to Marble Bar, Newman and Karijini but we will now spend at least two nights at CK.

This will be our first journey to the Kimberley and our travel within the region will include about three and a half weeks exploring the features of the GRR. This includes a trip to Mitchell Falls/Surveyors Pool. Even though I had already read a great deal about the Gibb River Road I learnt more again from your blog because of the detail and descriptions included. I sincerely hope that there will be a space for us at Mornington.

I really appreciate the time and effort you have put into your blog and for sharing the details of your travels with other people. It was a pleasure to read a well written and descriptive record of your experiences. I will now have to read your other blogs.

Happy and safe travelling.

PS: we are just about to fit new shockers to our 4WD and camper!

Dear Sheena

Thank you so much for your comments on our blog. It is lovely to know that you found it both useful and enjoyable. We put a lot of work into it – but it is a labour of love, because it helps us to relive the wonderful places and adventures we have had.

We hope you have a tremendous time in the Kimberley. Given that you love wildlife, we are certain you will. And you won’t regret those new shockers!

Best wishes

Peter & Nirbeeja