Kangaroo Island

At long last we visited Kangaroo Island (KI). In short, we absolutely loved it. Forget what you might have heard about the expensive ferry ride to the island (which is reputedly the most expensive ferry ride per kilometre in the world) and cost of travelling around and staying on the island (which isn’t so bad), it is well worth all the effort and expense. Our only complaint was that we weren’t there for long enough. We stayed just over a week, giving us enough time to sample most of what the island has to offer, but leaving us wanting more and vowing to return.

We were blessed with near perfect weather during our stay, allowing us to fully appreciate the beauty of the Kangaroo Island coastline, from the wild south which bears the brunt of the Southern Ocean, to the more sheltered and serene north.

Despite visiting during the school holidays, the crowds just weren’t there, and we often had places and beaches all to ourselves. Of course, anyone who knows us would be aware of our love of wildlife and wilderness, and Kangaroo Island more than delivered on those fronts. We were a little wary of the tourist brochures promising plenty of wildlife, but were blown away by just how much we encountered.

Unfortunately, and this is probably our only complaint about the island, a good deal of the wildlife we saw as we travelled the major roadways on KI was in the form of roadkill. It was horrifying to see so many dead wallabies and possums. These are mainly nocturnal creatures, so obviously many people travel the island at night, though with a resident population of only around 5000 people, plus tourists, you would wonder how so many animals would perish. Perhaps overambitious tour itineraries are to blame. Much of the agricultural centre of KI has been cleared, but thick native vegetation lines the roadways, and is a haven for wildlife, which continually crosses the road. We believe more should be done to educate visitors (and possibly residents) of the need to slow down at night. A simple message, though often ignored. The locals suggest that foreign tourists are largely to blame, coming as most do from countries with little wildlife, though we heard a few comments from locals to suggest that they are rather blasé about the roadkill problem.

Anyway, apart from that, we loved everything we saw. The western area, featuring the Flinders Chase National Park, was particularly spectacular. That area was hardest hit by the bushfires of December 2007, but has undergone a remarkable recovery, providing evidence of the resilience of the Australian bush. The scars of the bushfires are still evident, but so is the luxuriant regrowth and renewal of vegetation and abundance of wildlife.

It was reassuring to see so many live Tammar Wallabies and KI Kangaroos once we reached the west, and to be visited by Brushtail Possums at night. We camped in the Rocky River campground during our stay in the national park, and were entertained by the honking and courting displays of the large local population of Cape Barren Geese, and by the eerie calls of the Bush Stone Curlew at night. We also heard many Crescent Honeyeaters with their ee-jit ee-jit call during the day, though these elusive little blighters proved impossible for me to photograph.

A TINY BIT OF HISTORY AND BACKGROUND

The Aboriginal people once lived on Kangaroo Island. Archeological evidence suggests that they first inhabited the island at least 16000 years ago, at the time of the last ice age, when the island was joined to the mainland. They probably continued to live on the island until around 2000 years ago, though no-one knows how or why they left. To the Aboriginal people of South Australia, Kangaroo Island is now known as Karta, the Land of the Spirits (or Land of the Dead).

When White Australians first settled the island, they found the wildlife to be quite tame, as they had no reason to fear humans. As a result, much of that wildlife was ‘exploited’, and the local Sea-lions and Fur Seals were all but wiped out for their fur and fat.

Fortunately however, some of the early settlers had a different vision, and sought to preserve the wildlife of Kangaroo Island, much of which had become unique through its isolation. The island is home to many species or sub-species found nowhere else, such as a Kangaroo Island Tammar Wallaby, Kangaroo Island Kangaroo, the Glossy Black Cockatoo, the Kangaroo Island Dunnart and a sub-species of Red Wattlebird. It is testimony to the vision of those people that there are still no foxes and rabbits on the island, whilst they have caused widespread damage on the mainland. Other mainland wildlife species, such as Koalas and Platypus, were introduced onto Kangaroo Island early last century by people who realized, even then, that they might eventually become endangered on the mainland. And the Ligurian bee, a gentle and productive species originally from northern Italy, was introduced onto Kangaroo Island in the 1880s. Effective quarantine controls have preserved the bees, and they are now the only pure species of Ligurian bee in the world. Nirbeeja, as a connoisseur of fine honeys, can attest to their productivity, as can every available inch of our storage which now contains her KI honey purchases (oh, okay, we did also get some Bay of Shoals wines to keep me happy).

SEAL BAY

Of course, no visit to Kangaroo Island would be complete without an encounter with its famous Australian Sea-Lion colony at Seal Bay.

Seal Bay is a fine example of the way tourism and nature combine on KI, with both benefitting. Seal Bay has a huge number of visitors each year, yet the interaction with wildlife is controlled such that the Sea-Lions are not harmed, and their behaviour not (obviously) affected. A series of relatively unobtrusive boardwalks allow visitors good views of the Sea-lions on the beaches, in the water, and resting in the sand-dunes, yet also protect the animals from human interference.

The rangers conduct well-controlled, small group tours onto the beach for close encounters with the Sea-lions, where the well-being of the animals is of highest concern. You get close enough to the animals to come away with a great experience, but not so close as to put yourselves or them in jeopardy.

The tours are also highly informative, serving to educate visitors and by so-doing probably increase the long-term prospects of the animals. We learned from ranger Rod that the colony consists of around 1000 Australian Sea-lions, a great recovery from the 1800s when it was virtually wiped out by sealers. It is not all good news however, and the colony in now declining by 2 to 3 per cent per year. No-one knows the reason, though it is probably a combination of several factors, such as over-fishing of the waters in which the Sea-Lions feed, a long-term depletion of their genetic stock because the current colony was based on too few surviving individuals, and death caused by human debris – such as fishing nets, which entangle or strangle the Sea-Lions.

We’ve always had a bit of a laugh at the way Sea-Lions lie around like giant slugs on the beach and rocks. We now have a little more respect for them since learning that they swim out into the open Southern Ocean, 40 kilometres off the coast, diving off the edge of our continental shelf up to 1000 times over a three day period in search of food, before returning to Seal Bay for a well–earned rest. Even Sea-Lion pups endure these ‘fishing trips’, and can be seen returning to collapse on the shore, completely exhausted, several minutes behind their mother. It is definitely a case of survival of the fittest. When Sea-Lions are too weak or too old, they are taken by the Great White Sharks which infest our southern waters. We will laugh at them no more!

To watch some videos we took of the Sea-Lions of Seal Bay ‘doing their thing’, click on the following links:

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vgc3kHMoJGs

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=euwdLcCEsF0

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZYpALpUafFg

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QpsCQAzg2Bg

FLINDERS CHASE NATIONAL PARK

We travelled further west along the southern coast of KI to the huge Flinders Chase National Park, where we stayed for four nights. I’ve already mentioned some of the wildlife we encountered there, but there was so much more there as well.

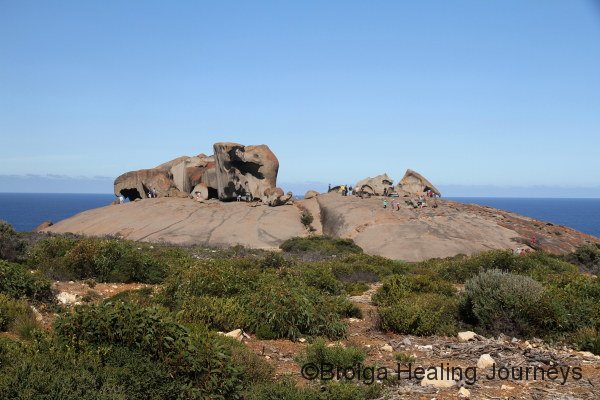

The park is famous for its landforms, such as the dramatic Remarkable Rocks and Admirals Arch. These are famous for a reason – they are simply spectacular places, the very air charged by the high-energy Southern Ocean pounding the nearby shores. At such places one feels totally alive and inspired.

As if the landforms weren’t enough, the coastline around Admirals Arch is home to a large colony of New Zealand Fur-Seals, nimbler and more playful than the Australian Sea-Lions of Seal Bay (I will resist any Trans-Tasman comments at this stage). We were entertained by these Seals for hours as they played, jostled, and generally busied themselves around the rocks and waves. What a life they appear to have.

We captured some footage of the Fur-Seals in action near Admirals Arch. Click on the following links to watch:

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6BzPSJvmMJs

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yhaFWQ3jd3Q

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=woM6nJx_bRk

Further west in the national park, we walked from Snake Lagoon to the mouth of the Rocky River on Maupertius Bay, and its secluded beach. We had this special place all to ourselves, well, almost. In fact we shared it with four Hooded Plovers, an endangered bird species now seldom seen along our southern coasts. Many signs around the South Australian coastline serve to make visitors aware of these birds and, hopefully, prevent visitors from interfering with their now rare nests in the sand-hills; unfortunately, we still saw people running their dogs off the leash along affected mainland beaches and others driving cars on beaches in supposedly protected areas on the mainland. So for us this was a reminder of the role national parks play in providing a safe haven for wildlife – this beach had no dogs, and no cars to endanger the plovers. We watched as the three adult Hooded Plovers and one juvenile ran and flew along the shoreline searching for food. May they prosper and multiply.

We captured some footage of the rare Hooded Plovers in the national park. Click on the following links to watch:

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wh4CYH6gDuE

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H2151LQ3Fp0

On the far west coast we visited Cape Borda Lighthouse. We are used to seeing statuesque lighthouses, with their tapered conical shape, but were met there by a short, squat, square one. The reason for that is simple – sitting atop the 180 metre high cliffs as it does, it has no need for further elevation. And, as the passionate, indeed totally manic lighthouse-keeper Mick kept telling us, it was the only ‘real lighthouse left on Kangaroo Island’. (We believe there must be some secret competition between Lighthouse tour-guides to provide the craziest, funniest tour, because we had earlier encountered a similarly memorable Scotsman as tour-guide at the Cape Willoughby Lighthouse on the eastern end of the island.)

The cliffs around Cape Borda provided magnificent views of the ocean below, almost calm on the day of our visit. The waters visible far below at Scotts Cove were the most brilliant blue I have ever seen.

To view videos of the daily loading and firing of the cannon at Cape Borda Lighthouse, click on the following links. The tradition of firing the cannon at the same time each day allowed passing ships to set their timepieces, an essential part of navigation in the days prior to GPS.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iW-W0g9Ilhk

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lsf4APeOFtU

THE LIMESTONE CAVES OF KELLY HILL CONSERVATION PARK

On our last full day, the only rainy one we encountered on KI, we visited Kelly Hill and its limestone cave complex. These caves are drier than most limestone cave systems, because they rest within large, ancient sand-dunes within a hillside. As a result, the limestone formations are finer and more delicate than usual, and quite beautiful. They were discovered in the 1885 by a stockman, who fell into a sinkhole while riding his horse Kelly. The stockman climbed to safety, but his horse remained below, believed dead, though her remains were never found. The area - Kelly Hill – was named in the horse’s honour. It wasn’t until 1925 that the cave formations beneath Kelly Hill were discovered, and almost immediately they were put under protection. The pristine state of the limestone formations within the caves today is a wonderful legacy of this foresight.

The caves not only contain beautiful and delicate stalactites, they also contain some of the finest bone and fossil specimens of mega-fauna in the world, and many examples of helictites – limestone formations that appear to defy gravity by growing at odd angles. Speleologists have no explanation as to how helictites form, though a recent theory suggests that it may be through capillary action. All we could do as visitors was stand and marvel at the beautiful subterranean world of the Kelly Caves.

We climbed to the surface, and as we took the bush path towards the carpark I heard movement in the nearby bushes and was thrilled to see a blonde-spined, Kangaroo Island Echidna, a sub-species which had hitherto eluded us. (Nirbeeja suggests that the Echidna must be my animal totem, because I seem to find them everywhere, even spotting them from moving vehicles at night. She adds, I trust with tongue in cheek, that this totem may explain why I’m often a bit prickly to deal with!)

To view a short video we took of the Echidna, click on the following link:

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r_g5VkW2Mnw

A FINAL SURPRISE

Not a little sadly, we headed east again to Penneshaw for a final night before our ferry ride back to the mainland and its mayhem. We drove across the island, taking in the giant Yacca (grass-trees) and Sheoaks, watching the Superb Fairy Wrens flit too and fro.

As we set up camp in Penneshaw, I heard my name called out, and who should be there, but Shannon, a lady I know from Canberra, about to tour the island with her husband and another couple. We had a lovely time catching up and hearing some news from home. A small camping ground on Kangaroo Island was the last place I expected to find someone I knew, but as Nirbeeja always says, ‘big country, small world’.

Our final encounter with KI’s wildlife was by way of a nocturnal tour to view the wild Fairy Penguins of Penneshaw. Their numbers are higher than at Granite Island near Victor Harbour on the mainland, but they are nevertheless in decline. Hopefully the isolation and long-standing tradition of protecting wildlife on Kangaroo Island will hold them in good stead.

Peter

24 April 2011

Postscript:

Readers of our blogs may tire of learning about the plight of wildlife in the latest area we have visited. I include this information in our blogs in the hope that it might inspire readers to make a difference in the world. We often despair for Australia’s wildlife, and that of the globe more widely. Much of humanity continues blindly on its selfish and destructive path, not only harming itself, but leaving a trail of extinctions in its wake. And even on Kangaroo Island, which is a shining light in a troubled natural world, wildlife still faces a battle, with Sea-Lions and Fairy Penguins on the decline, and the ugly taint of roadkill there for all to see.

Nirbeeja and I commenced our travels almost four years ago, naming ourselves Brolga Healing Journeys, with the intention of sharing our Yoga, Tai Chi and Natural Medicine practices with the people we met on our travels. But we have shifted our focus from helping humanity to saving our wildlife. Perhaps the inclusion of a native Australian bird in our business name was more appropriate than we realised at the time.

Hi Pete and Nirbeeja

Wonderful to catch up through your blog and wonderful gallery of photos – just fantastic images of KI. Nice to know that while you’re saving wildlife on the ground from your side, I’m doing what I can in Government! Great to see you earlier this year, sorry it was so short. Cheers Mark.

Hi Mark,

Was great catching up with you as well, and yes, it is good to know we are all doing our bit! Hope those national parks are behaving themselves! Cheers

Pete & Nirbeeja

Regarding roadkill on KI. I believe you are correct, the locals tend to drive faster than the tourists and are responsible for more roadkill. My experience working for Parks in Flinders Chase is that the International visitors are very responsible on the roads. Australian tourists also tend to be more respectful of wildlife on the roads.

On a positive note, there are now more signs asking people to drive carefully due to wildlife. The obvious option of lowering the speed limit on the island has not been put forward seriously yet. It would take a brave official to suggest that. Right now the focus is getting the island community to accept Marine Parks. There is an interesting dynamic on the island between the farming/fishing community and the enviornmental groups. Education is a slow process, much emotion needs to be gotten through before an agreed position is attained. The same will happen when the discussion turns to the issue of roadkill

John Hodgson

Thank you for your comments John. It is really helpful to get to hear the local perspective. Good luck with the work on Marine Parks. It seems KI is a microcosm of many of the issues we face as a broader community. We hope to return to KI soon.